Ogu Umunwaanyi: The Women’s War

By: Patricia Hagen

Abstract

In Southeastern Nigeria on the 24th of November of 1929, the British witnessed the largest uprising they had seen anywhere in Africa up unto this point. Ten thousand women rallied together from six different ethnic groups across Igboland to protest British Colonial rule, specifically the taxation of women. The mostly non-violent protest lasted thirty-eight days spanning from November to December, and resulted in the changing of the political structure in British Nigeria. The participating women played an instrumental role in asserting the authority of native Nigerians to the British government.

Ogu Umunwaanyi: The Women’s War

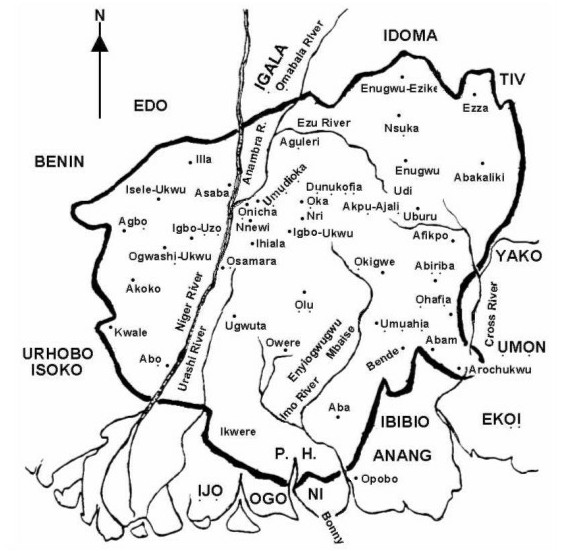

In an effort to clarify some of the language in this paper it is important to identify some of the terminology used as it creates a greater understanding of the fundamental issues at play. First, Igboland is a region in South East Nigeria that attempted to be independent from Nigeria, both pre- and post-colonialism. It consists of many smaller towns, each with their own identities. The regions of Aba, Bende and Okigwe were the main epicenters of the protests. Second, the events in November of 1929 are called different names by different people. Native Nigerians referred to the uprising as Ogu Umunwaanyi, which directly translates to The Women’s War in english. The British however referred to the event, in writing and in speech, as the Aba Riots (Matera 1). It is important to recognize the difference between these two perspectives, because it is conceivable that the chasm between their understandings contributed significantly to the events to escalate the way that they did. The women of Southeastern Nigeria were from many different ethnic groups, so to describe them all as Aba is misinformed. Also, the word “riot” implies a violent disruption of the peace, and it is clear from all reports that the women involved were not violent, with the exception of burning empty buildings. In light of this, the phrase Women’s War or Ogu Umunwaanyi will be used when referring to this event.

The British occupied Nigeria in 1885 and established the first Christian mission in Igboland. Over the next forty-five years, British rule increased incrementally. It began with the conversion of native peoples to Christianity, and then to the introduction of the British pound. In 1916 the British outlawed native currencies, and introduced taxes. First the taxes only applied to goods in the marketplace, but then the British began taxing the belongings of men, beginning with palm oil. When the British attempted to place a tax on women for their belongings, typically goats, tensions escalated to all time high (Matera 1).

The British occupied Nigeria in 1885 and established the first Christian mission in Igboland. Over the next forty-five years, British rule increased incrementally. It began with the conversion of native peoples to Christianity, and then to the introduction of the British pound. In 1916 the British outlawed native currencies, and introduced taxes. First the taxes only applied to goods in the marketplace, but then the British began taxing the belongings of men, beginning with palm oil. When the British attempted to place a tax on women for their belongings, typically goats, tensions escalated to all time high (Matera 1).

It is still unclear if the British actually intended to tax the women of Nigeria, but the idea on its own was certainly enough to spark a one month uprising. It is also unclear if the protests were really about the prospect of taxation. This lack of clarity is attributed to the lack of written records regarding most regions in Africa during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. By most accounts it is the British taxing of women that was responsible for the Women’s War, however with a broader understanding of the pre-colonial social structure it appears that the Igbo women were more concerned about their social standing and the British disregard for their personal authority.

Every aspect of life in pre-colonial Igboland required mutual interdependence. This mutual interdependence existed not just between men and women but between the human world and the spirit world. It was viewed that all things- work, politics, and creating life- would not be possible without the input of all members of society both past and present. Women and men sat together as elders on commissions and were both responsible for governance. Women who were too young to govern formed vast social networks and regularly boycotted or protested to affect political change (Bernhardt 1). Unlike many other ethnic groups of the region, the Igbos didn’t institute chiefs that presided over all the others. Instead the whole society shared the decision making, resulting in one of the only true democracies of the time (Agozino 285).

This style of governing proved very difficult for the British colonials, who ruled indirectly. Typically when the British implemented indirect rule, they would utilize the existing power structures to carry out the demands of the crown. In Igboland, however, there were no single ruling entities, thus the British created Warrant Chiefs to be liaisons between their village and the crown. Not surprisingly, those that accepted the position of Warrant Chief held little to no moral leadership within their ethnic groups, as the majority of people in Igboland were united as one to oppose the new imperialist rule (Agozino 285). What’s more is that once these individuals were given power, they abused it by mimicking the colonial ways of ruling. They oppressed women by demanding women for wives, where Igbo women previously held the right to deny a suitor at their leisure, and they stole property from women for their own personal gain (Bernhardt 2).

The Warrant Chiefs’ oppressive acts ignited a movement among the women of Igboland. Women utilized their vast social networks by communicating in market squares and spreading news of their frustrations as far as word would travel (Matera 7). For many months after the taxation on men’s property was implemented, women suspected a tax would be levied on them, thus their frustrations grew until finally in Oloko their suspicions were confirmed. A Warrant Chief named Okugo came to a woman by the name of Nwanyeruwa’s home and told her to count her animals. It is said that she responded with, “Was your mother counted?” which referred to the tradition of women never being counted as they were not supposed to be taxed. He struck her body angrily and she left to find her women’s network in Oloko. Next, the women sent out palm leaves to neighboring villages which invited them to come and protest the oppressive behavior of the Warrant Chiefs and the impending taxes at the district administration office in Okolo. The women were asked to pass the palm leaf to at least one other woman upon receiving it, creating a chain mail effect that reached the 10,000 women who arrived in Oloko on November 24 (112).

At the district administrative office, Captain John Cook ordered Warrant Chief Okugo to offer written assurance that he would indeed not tax the women of Igboland. He did, but fueled by humiliation and frustration he then took eight women hostage and harassed them (Bernhardt 3). Outraged, the women stayed for several more days demanding that Okugo be dismissed from his position as Warrant Chief. To the women’s surprise the British conceded, dismissing Okugo from his position and sentencing him to two years imprisonment.

News of the women’s successes travelled across the region and protest erupted across 6,000 square miles of neighboring villages. The Igbo women had a history of battling male oppression, usually in the form of domestic violence, by “sitting on a man.” To “sit on a man” the women of a community would come together and dance circles around the man who had disrespected a women and sing to the spirits (Matera 1). This was done to force the man to reflect on what he had done. They would never touch him nor speak to him, but simply sing and chant their demands for, essentially, an agreement to change his ways or for the spirits to make things right. They would sing day and night, loudly, to disrupt the man’s day, forcing him to acknowledge their presence. Sometimes the women would burn down the man’s hut too, hence the burning of a few British offices during the protests. This ritual of “sitting on a man” could last for days or weeks, depending on the man’s will to oblige to the demands asked of him, but in the case of the Women’s War, the process of “sitting on” lasted well over a month.

In the month long protests, the women were wildly successful. They replaced almost all the Warrant Chiefs as well as drove out “nearly all the whites” (Azikiwe 178). Many of the Warrant Chiefs who were dismissed, also faced criminal charges and were convicted of assaults against women. Others stepped down voluntarily after being worn down by the constant attention of women “sitting on” them. The women pushed for the British to agree to lift the tax on men, to not place a tax on the women, and even led the way for a new form of governance called “mass benches.” Mass benches consisted of a panel of locally elected officials, which returned some of their self governance to the Igbo people.

What ended the protests wasn’t the massive successes that were achieved. Instead, on December 16, 1929, the British officers, “overwhelmed and confused by all the commotion,” fired into a crowd of women in Okigwe, killing 47 women and injuring 31 more (Matera 3). The officers then threatened more violence if the protests continued, causing the women to disassemble. It is important to note, however, that this only happened after the women of Southeastern Nigeria made it clear to the British that they were not invisible, and that they had a voice and a will stronger than the English ever imagined.

Perhaps if the British understood the culture of the protesters, they would have recognized that the women were fighting for the very thing the British had fought so hard for themselves, democracy. Shortly after the shooting, in January 1930, the British held the Aba Commissions where a panel of English judges listened to testimonies in order to file a report. One of the judges, Mr. Graham Paul, is quoted as saying, “No one listening to the evidence given before us could have failed to be impressed by the intelligence, the power of exposition, the directness and the mother-wit which some of the leaders exhibited in setting forth their grievances. And the lessons learnt from their demonstrations should be taken to heart,” (Matera 4). According to Matera, Mr. Graham Paul was the exception, but at least the humanity of the Nigerian women did not go completely unnoticed.

This wasn’t the last time that women in Nigeria banned together in unique, peaceful protest. The overall success of this movement inspired multiple tax protests in the 1930’s and 40’s, the Oil Mill Protests of 1940, and most recently the protesting of ChevronTexaco’s Nigerian unit in 2002. In 2002, hundreds of women stormed a ChevronTexaco refinery, shut it down and threatened to remove all their clothes unless their demands were met. ChevronTexaco listened to them, and within a couple of weeks had agreed to hire local men, build a community center, a school, and roads in addition to providing microcredit loans for women to start their own businesses (BBC News).

This wasn’t the last time that women in Nigeria banned together in unique, peaceful protest. The overall success of this movement inspired multiple tax protests in the 1930’s and 40’s, the Oil Mill Protests of 1940, and most recently the protesting of ChevronTexaco’s Nigerian unit in 2002. In 2002, hundreds of women stormed a ChevronTexaco refinery, shut it down and threatened to remove all their clothes unless their demands were met. ChevronTexaco listened to them, and within a couple of weeks had agreed to hire local men, build a community center, a school, and roads in addition to providing microcredit loans for women to start their own businesses (BBC News).

Protests are central to the social processes, and in turn the social reality, of many Nigerians. This is in part due to the low economic standing of the majority of their citizens. When people do not have access to large sums of money or economic influence, they use what they have, which is often their voice. It is important to note that there are few scholarly accounts of sub-saharan African protest, not because of the lack of protesting, but in part due to a lack of higher education institutions as well as a lack of free media. Nigeria has a relatively free media, ranked “partly free” at 105 out of 196 rankings, and active civil society groups, thus reports of uprisings are more popular than in places such as Eritrea, for example, which was ranked 194 out of 196 countries in the 2013 Freedom House report.

This narrative is vital to the understanding of colonialism in Nigeria and modern women’s movements. Too often the narrative surrounding European imperialism is eurocentric, often implying that Africans did very little to resist colonization. Ogu Umunwaanyi is proof that this narrative is simply not true and that democracy is not a western concept. The lack of resources surrounding this topic also demonstrates the centuries long impact of western imperialism, as the victor usually writes the history. However, globalization is taking on new forms in the twenty-first century. Combined with increasing internet access and accessibility to higher education, stories of struggle will continue to rise from the shadows and add heart to a sometimes heartless history.

References

Agozino, Biko. “Revolutionary African Women: A Review Essay Of The Women’s War Of

1929: A History Of Anti-Colonial Resistance In Eastern Nigeria.” Journal Of Pan African Studies. Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2011. Print.

Akuta, Chinedu. “What Igbos Want for Southeastern Nigeria.” Most Contributed; Most

Neglected. WordPress. 20 Feb. 2014. Web. 22 Nov. 2014

Azikiwe, Ben. “Murdering Women in Nigeria.” The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races.

W.E.B. DeBoise. 30 May, 1930. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

Bernhardt, Arielle and Max Rennebohm. “Igbo Women Campaign for Rights (Women’s

War) in Nigeria, 1929.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. Swarthmore College, 15 July, 2007. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

“Deal Reached in Nigerian Oil Protest.” BBC News. BBC News, 16 July, 2002. Web. 22

Nov. 2014.

Evans, Marissa. “Aba Women’s Riots: November/December 1929.” Black Past.

Blackpast.org, 2011. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

Global Press Freedom Rankings. Freedom House, 2013. Web. 6 May, 2015.

Matera, Marc, et. al. The Women’s War of 1929: Gender and Violence in Colonial

Nigeria. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. Print.

Author Bio

I have had the fortunate opportunity to work and live in China and Thailand where I helped open an international preschool and trained teachers to work with Burmese refugee children. When I realized that I wanted to have a larger impact on the state of education, I moved back to the United States and worked to complete a BSS in Global Studies at St. Edwards University. I have since worked to further my understanding of Sub-Saharan Africa and its role in the larger global political economy with the intention of improving U.S. relations with developing nation-states.

I have had the fortunate opportunity to work and live in China and Thailand where I helped open an international preschool and trained teachers to work with Burmese refugee children. When I realized that I wanted to have a larger impact on the state of education, I moved back to the United States and worked to complete a BSS in Global Studies at St. Edwards University. I have since worked to further my understanding of Sub-Saharan Africa and its role in the larger global political economy with the intention of improving U.S. relations with developing nation-states.