By: Victoria Jimenez

ABSTRACT

This report examines the role of water management in the city and greater community of Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Tegucigalpa has encountered severe problems with drinking water shortages, inadequate water management programs, and unethical distribution of water. As Tegucigalpa continues to grow at a fast rate, urbanization plays a large role in the future of Tegucigalpa’s water supply. By examining the roles that are present in Tegucigalpa’s water crisis, I am able to clarify the broad current problems and possible solutions that could be implemented.

Tegucigalpa, Honduras

Tegucigalpa is the national capital city of the country Honduras, located in Central America southeast of Guatemala, north of El Salvador, and northwest of Nicaragua. It is located in a valley that is completely surrounded by large mountains. Tegucigalpa is located within the Choluteca River Basin and Zone South of the country, with an average elevation of 1,200 meters. Central consists of five rivers sub Guacerique, Large, Sabacuante, Tatumbla and Chiquito. These rivers meet in Tegucigalpa and form the Choluteca River.[1] Tegucigalpa was first inhabited by indigenous people, specifically Mayan, and was later established and colonized in the late sixteenth century by the Spanish. It started out as a silver and gold mining industry, and today some of their major manufactures are textiles, sugar, and tobacco. It became the permanent capital of Honduras in 1880, and in 1930 merged with the city of Comayagüela, which was then located across the Choluteca River to form the Central District. The city is one of the few major cities in the world to lack a railroad system.[2]

The city is filled with all types of poverty and corruption. Honduras suffers from rampant crime and impunity for human rights abuses. The murder rate was [again] the highest in the world in 2014. The institutions responsible for providing public security continue to prove largely ineffective and remain marred by corruption and abuse, while efforts to reform them have made little progress.[3] Their political system follows suit. Originally set up as a democracy, the judicial system is constantly corrupted with intimidation methods and political interference that keeps them from doing their job. In 2012, four out of five of their Supreme Court Justices were dismissed, and have received numerous death threats, police brutality, and harassment. Their attempt at creating a new judiciary system is quickly failing due to their inability to establish a specific council.

From drinking water shortages, to financial burdens and food crisis, Tegucigalpa has seen it all. Many people from the impoverished community live in the mountainous region of Tegucigalpa (also recognized as the greater Tegucigalpa area) and face severe consequences such as landslides, flooding, and soil erosion. As for their economy, about one out of three of the capital’s population is unemployed.[4] Honduras is a lower-middle income country, the third poorest country in Latin America, with approximately 51% of the population living below the national extreme poverty line. Approximately 30 percent of the population live below the international poverty line of US $2 per day, while 18 percent live below US $1.25 per day. Poverty is particularly acute in rural areas, where many households are landless or land-poor.[5] Unfortunately, the capital’s industries cannot keep up with the amount of people that are migrating into the city. Another main concern regarding their economy includes their immense infrastructure damages from Hurricane Mitch. This hurricane struck in 1998, but has left a lasting footprint of devastation on the city.[6] Countless physical infrastructures are still waiting to be repaired, and it has put a huge economic burden on the city.

Honduras is governed by a democratic republic. On the 26th of April 1961, SANAA (Servicio Autonomo Nacional De Acueductos y Alcantarillados translated: National Autonomous Aqueduct and Drainage Service) was created as the authority for the development and operation of the water supply and sewage systems for Honduras.[7] Run by the state government, they are responsible for providing water to the citizens of Tegucigalpa, but unfortunately have fallen short of this responsibility due to inadequate financial resources and explosion in urban expansion.

If you were able to pinpoint a specific problem with Tegucigalpa, the most common and popular would be their shortage of clean drinking water supply. There are many contributing factors to this problem. The physical nature for the city, for example, is a valley. It is surrounded completely by mountains, which poses as a problem in itself with things such as landslides, flooding, and sediment and rapid erosion buildup. Add this with an absence of a storm water management system, and you have a very poorly equipped city for natural disasters, such as the unexpected landslide or tropical storm.

Hurricane Mitch plays a large role in the shortage of water supply in Honduras as a whole, but especially Tegucigalpa. The flooding overwhelmed the city, and accounted for the demolition of 10 out of 12 of Tegucigalpa’s major bridges. Many other infrastructures were also destroyed, including roads, the small amount of infrastructure that was available for storm water damage, houses, industrial water containers, and more. With the floods of Hurricane Mitch, reservoirs were also affected by siltation. The large amount of entrained solids caused high turbidity in the raw water for a long time. The solids then settle and accumulate for the silt at the bottom.[8]

Including Hurricane Mitch, other factors to be included are the rapid urbanization, deforestation, and above all, inadequate water management. Their first issue begins with surface water. Owned by the nation, surface water is hardly caught, and contains toxins and pollution due to agriculture, runoff, polluted waters, and sewage. The rivers flowing through the cities of Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela receive a lot of organic matter. The reservoir Laureles is most affected, causing changes in water quality, bad odors, and sludge buildup in the background (especially in the dry season due to low flow). The situation becomes more serious, since anoxic conditions and high nutrient concentration (including phosphorus) and minerals (such as iron and Manganese) generate treatment problems. During the rainy season, due in part to deforestation, and especially after Hurricane Mitch occurred, much sediment entrainment increased, causing an increase in turbidity and color in the rivers and streams that supply Dam Concepción, Los Laureles, Tatumbla and Rio Sabacuante.[9] An excerpt from “Honduras: The Case of Drinking Water Supply in Tegucigalpa” by PROFOR gives a brief of Tegucigalpa’s groundwater technicalities:

While several watersheds provide Tegucigalpa with water, the city relies on just two reservoirs—Concepcion and Los Laureles—to supply drinking water to more than one million inhabitants. Of the two, only the Los Laureles reservoir is located in the Guacerique watershed…Since [Hurricane] Mitch, the reservoir has lost an estimated 15 percent of its storage capacity due to increased sedimentation. The watershed is important because it supplies 25 percent of the water supply in Tegucigalpa. [10]

Many times groundwater contains a high mineral content, making the water undrinkable until levels are restored.

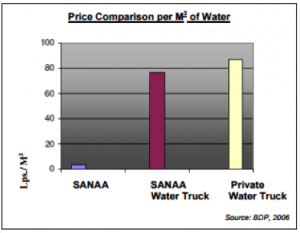

While the root of the problem is the supply of water, there is equal, if not more, dependency on the demand. 38 percent of Tegucigalpa’s population lives in extremely high regions (in the surrounding mountains) and are unable to receive proper water lines. Because of this, they rely on water trucks to bring them water, not only for their own personal use, but also for agricultural use. The amount of water they receive is astonishing. The paradox of low-income peri-urban communities that lack connection to piped networks in Tegucigalpa, and indeed across the developing world, is that residents are obligated to pay up to 100 times more for unreliable service delivery of questionable water quality than those communities that are connected to a conventional system[11], much like the more urbanized sections of Tegucigalpa, residing in the depression of the mountains.

In 2005, SANAA registered 113 communities serviced by water trucks that were either privately operated or owned by SANAA itself. These water trucks pay approximately Lps. 0.025 per gallon which is then sold at Lps. 0.40 per gallon. Based on these figures and the number of water trucks in operation, it is estimated that the residents of Tegucigalpa’s peri-urban communities spend between $US6.9-9 million dollars annually, which amounts to up to 9 times the average annual revenue generated by SANAA. [12]

These numbers are extremely high, especially considering the poverty level at which these citizens are already suffering. The picture below shows an example of the size of truck delivering the water, and the graph helps to put into perspective the audacious difference of prices.

When you look at numbers and statistics, it continues to go downhill. A recent study of their water states that urban services in Tegucigalpa are deficient, with a nominal coverage level of 83% for water supply, 68% for sewerage, 80% for solid waste, and only 17 percent for wastewater treatment. Water sources do not cover the city’s demand; recent estimations have shown the city’s water supply has a deficit of about 60 million cubic meters per year or about 2 cubic meters per second, mostly during the dry season (close to 50% of total demand). As a result, severe water restriction programs are imposed during most summers, leading to highly discontinuous water service. Regarding sanitation, only about 68% of the population is connected to a sewer system while most others rely on septic tanks or traditional latrines.[13]

So who is responsible for the cleanliness of water and adequate supply? A large portion of this falls directly to SANAA. Due to SANAA’s inability to thoroughly address Tegucigalpa, the city has undergone a number of water problems, including untreated sewage, lack of management of toxic or hazardous waste, and lack of proper watershed management as stated above. Though Hurricane Mitch is responsible for a large amount of infrastructural damage to the city, Tegucigalpa’s problems with water began long before the hurricane hit. Water has become an issue for the city since the early 1960s, when the population really started to grow. This is the same time that SANAA was introduced into Tegucigalpa. In 1961, SANAA realized that Tegucigalpa needed a reservoir to guarantee water supply to their 164,941 new inhabitants. In May of the same year, the construction of a new water reservoir in the Guacerique River was proposed as the best solution and in 1972 SANAA decided to build the reservoir. However, the project faced financial difficulties and it never came to fruition thus leaving Tegucigalpa with an unsatisfied water demand.[14] The absence of this infrastructure did not pose as a threat to Tegucigalpa in the 1960s, or even 1970s, but today in 2015, it poses a huge threat. The population of Tegucigalpa currently sits at around 1,100,000. This population is expected to double within the next 10 years. When Tegucigalpa is already having significant issues with water supply, what are they supposed to do with 1 million more residents to supply water to? That is what the city wants to know, and that is what SANAA can’t seem to figure out.

Lack of investor capital is what initially prohibited SANAA from building the much needed dam (previously mentioned as “Guacerique”) in order to increase the supply of water to the capital city. This angered the national government, putting the city of Tegucigalpa in a very sensitive situation. With no money, and no water, the city continued to grow in their need for new infrastructure and financial help.

To finally combat this serious issue, SANAA proposed a project based on “Guacerique,” as “Guacerique II.” Approved by President Porforio Lobo Sosa, “Guacerique II” was given the green light to carry out the work in a catchment area of at least 189 square kilometers. In this area, an earth dam will be built with concrete face capable of storing 75.7 million cubic meters of water[15]. The project was adopted with international support from South Korea. The new dam will allow the water treatment plant in Los Laureles to produce the past 20.81 million cubic meters of water to 44.46 million cubic meters. The dam will also expand the distribution circle of the water, which currently only covers 30% of neighborhoods in the Central District (not including greater Tegucigalpa whatsoever). The investment to concretize the megaproject is estimated at $108 million, which is projected to be managed through the central government, public-private partnership, gifts or loans from international organizations[16]. This project is to be funded by the International Cooperation Agency of Korea (KOICA) and will hopefully expand the drinking water supply. It is promised to be lined with concrete to prevent leakage, and to help flush out the usual sediment and pollution that Hondurans face within their drinking water. This project has been promised, but there has been no sign of development thus far. They also have two obstacles: the promised project is not projected to be finished until 2018, and the Municipality may not agree with the proposal.

The two big stakeholders in this issue are SANAA and the Municipality of Tegucigalpa. SANAA, appointed by the national government, has many downfalls. One of the first to be considered is their affiliation with the Central Government. The Central Government, known to be incredibly corrupt, is the head of SANAA and all of it’s primary decisions. In Honduras, newly-elected presidents will reward those who supported him during the election campaign by offering them administrative offices, often regarded as the “spoils system.” This includes the position of the manager of SANAA. This corrupt system has led to a loss in continuity of the running and planned programs, the recruiting of the job seekers who worked during the elections for the victorious party in positions that were not vacant; therefore increasing the payroll and weakening SANAA financially, and the lack a sense of identity between employees and the company who realize their job would be threatened in the next electoral period. SANAA also employs more personnel than needed (14 employees per 1000 connections in Tegucigalpa; the average in other cities in Honduras is 4)[17]. Again, with each new election, new employees are recruited for political reasons and the trade union (SITRASANAAYS) protects already recruited employees from being fired. This excess of personnel is draining financial resources and compromises overall efficiency [18]. The Central Government also has a large amount of power when it comes to establishing the price of water. This questions the theory of the Right to Life[19]; is it vital for citizens to have access to water, or more important to receive financial gain?

Municipality puts this to the test frequently in Tegucigalpa. In an interview of Tegucigalpa citizens, an interviewee stated, “The municipality and SANAA have traditionally been antagonists, and there has been little cooperation.” Interviewees mentioned a conflicting relationship between SANAA and the municipality, for example, when the municipality authorizes settlements in high or in protected areas of the city. Additionally, SANAA has to invest resources creating and updating a database of the new constructions in the city, information handled by the Municipality[20].

In order to analyze these two stakeholders, one must understand the basis of the disagreement: the corrupt government. Though Honduras is set as a democracy, the corruption in the government stems from a national to local level. The rich simply have more say in these matters than those in poverty. Taking this into consideration, most policies that SANAA sets up are to first benefit those with power and money, and secondly to benefit the remainder of the population. Though most of “upstreamers” in Tegucigalpa are impoverished, they do not receive the same rights as a person might if they lived in the United States, regardless of financial standing. The “downstreamers” are the ones with the most easily accessible water. This is shown through the clean water exports taken within the city. As shown in the previous graph, SANAA and private vendors continue to exploit people in poverty with a small amount of water that they are then forced to share. This brings Amy Hardberger’s “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Water” into the picture. The Honduran government and Tegucigalpa’s local authority highly regard “accessibility” over “delivery” [21]. The secondary effects that arise with lack of proper delivery of water include reduced schooling, inability for family to earn living due to inadequate financial demands, and reduction of livestock and farming. This overall is a domino effect. It does not just affect greater Tegucigalpa, but all of the city. A solution must be made that benefits all of Tegucigalpa.

My tentative solution involves the implementation of the Guaderique reservoir and dam with financially feasible and consistent delivery of water controlled by SANAA. Private vendors will not be used unless screened and monitored by SANAA employees. This will prohibit any unreasonable prices from being charged to those that already lack any sort of pipeline for themselves. An infrastructure needs to be built promptly in order for citizens to claim their right to water. The reservoir needs to be lined with concrete so that no leakage of pollution or runoff is possible, and it needs to be fixated with the first purpose to serve those that have been severely overlooked in the past. The main drive behind this reservoir is to supply water to those that it never is able to reach.

There needs to be distributive justice implemented so that there is an equal approach to these water resources and opportunities. When an economic group makes up the majority of your population, you have to try to provide to them as much as you can. With pipelines unable to reach up into the mountainous regions of Tegucigalpa, these are the people who need it the most. The median household income of a Tegucigalpa citizen is L.81,712 (US$5,309) [22]. That’s a little over $445 USD per month, and $14 per day. These citizens are not able to pay the inflated rates for the price that that private vendors are selling their water.

Another idea that is worth considering is the concept of decentralization. Decentralizing from the dominating SANAA will allow the Municipality more power, knowledge, and decision-making in water management. I do not think that SANAA should be dismissed, however, if the municipality had more say in their citizen’s interest, I believe that the reservoir would have a better chance in being built. It is the municipality that will push forward the agendas of their local government, and unfortunately that is not a trait nor luxury that SANAA has, being controlled on a national level. If Tegucigalpa decentralized their water management, it would shed light on the problems that are so often hidden based upon economic status, and bring ease to the problems that desperately need to be recognized at a local level, instead of dealt with as just another national issue.

Although my plan seems a bit far-fetched, it is mildly feasible. It is financially out of reach due to the poverty level at which most of the receipts live in, but that is completely attributed to the economic section of the city which it is projected to cover. Overall, the project will cost close to $225,630,000 to complete. To develop this reservoir, Tegucigalpa will need to be dependent on grants and federal funding. They are just a slightly bit over budget when it comes to greater Tegucigalpa’s financial shortage.

Tegucigalpa has faced inadequate water supply and management for over 50 years and it cannot go on any longer. With such a rapidly growing population and urbanization, Tegucigalpa simply cannot provide for all of its citizens with two small reservoirs, both of which are currently polluted and continue to be contained with toxins and insufficient levels. Constructing a new reservoir is the best and most basic solution for their problems. I can only hope that Tegucigalpa can create an approach which appeals to their poverty-stricken population as well as their financially-stable. With the right management and the right decisions, Tegucigalpa can turn their accessibility of water into fair and justified delivery of a right to life.

[1] “Assessment of Causes Leading to an Insufficient Water Supply in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Dr. Lourdes Reyes Patricia Nassar. (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[2] “Tegucigalpa.” Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia (2015): 1p. 1. Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[3] “World Report 2015: Honduras”. Human Rights Watch. (2015) Web. 28 Nov. 2015

[4] Ballaro, Beverly. “Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Salem Press Encyclopedia (2015): Research Starters. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[5] “Local Institutions Matter: Decentralized Provision of Water and Sanitation in Secondary Cities in Honduras” Pearce-Oraz, Glen Dr. (2003) Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[6] Ballaro, Beverly. “Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Salem Press Encyclopedia (2015): Research Starters. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[7] “The World’s Water.” Gleik, Peter H. (2004) Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[8] “Assessment of Causes Leading to an Insufficient Water Supply in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Dr. Lourdes Reyes Patricia Nassar. (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[9] “Assessment of Causes Leading to an Insufficient Water Supply in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Dr. Lourdes Reyes Patricia Nassar. (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[10] “Honduras: The Case of Drinking Water Supply in Tegucigalpa” PROFOR (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015

[11] “Integrated Urban Water Management Case: Tegucigalpa.” The World Bank (2012): Water Partnership Program. Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[12] World Bank. (2002). Urban Services Delivery And The Poor: The Case Of Three Central American Cities. No. 22590. Washington DC. World Bank.

[13] “HN Water and Sanitation Sector Modernization Project.” The World Bank. (2012) Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[14] “Assessment of Causes Leading to an Insufficient Water Supply in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Dr. Lourdes Reyes Patricia Nassar. (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[15] “Aguas de San Miguel Could Replace SANAA”. El Heraldo. (2013) Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[16] “New Reservoir Guacerique II Should be Ready in 2018”. El Heraldo. (2015) 28 Nov. 2015.

[17] ERSAPS, Agua y Saneamiento en Honduras Indicadores. Edición 2009. 2009, ERSAPS: Tegucigalpa.

[18] “Assessment of Causes Leading to an Insufficient Water Supply in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Dr. Lourdes Reyes Patricia Nassar. (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[19] “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Water”. Hardberger, Amy. (2005) Print. 28 Nov. 2015.

[20] “Assessment of Causes Leading to an Insufficient Water Supply in Tegucigalpa, Honduras.” Dr. Lourdes Reyes Patricia Nassar. (2015). Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

[21] “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Water”. Hardberger, Amy. (2005) Print. 28 Nov. 2015.

[22] “Housing Policy in Honduras: Diagnosis and Guidelines for Action” Angel, Shlomo Dr. (2002) Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

AUTHOR BIO

Victoria Jimenez is originally from Seguin, Texas. She is currently an Honors student at St. Edward’s University where she is studying to receive her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Acting. Alongside her undergraduate career, she has worked various internships in the business and tech startup industry. Upon graduating, she hopes to continue her studies into graduate school where she plans to pursue an MBA in Management. Her overarching post graduate goal is to work to create more opportunities and leadership positions for latino women in the entertainment and business industry. In her spare time she likes to spend time with her family.

Victoria Jimenez is originally from Seguin, Texas. She is currently an Honors student at St. Edward’s University where she is studying to receive her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Acting. Alongside her undergraduate career, she has worked various internships in the business and tech startup industry. Upon graduating, she hopes to continue her studies into graduate school where she plans to pursue an MBA in Management. Her overarching post graduate goal is to work to create more opportunities and leadership positions for latino women in the entertainment and business industry. In her spare time she likes to spend time with her family.