Historical Development and Cultural Contexts: Rwanda

Prior to European colonization, there existed a mainly tribal social system that was comprised of the Tutsi and Hutus. The elite social strata was made of the Tutsi cattle herders, and the lower social strata was comprised of the poorer farmers called the Hutus. In this social system, it was possible for the Hutus to move social classes and become Tutsi if they were wealthy or owned a large quantity of cattle.

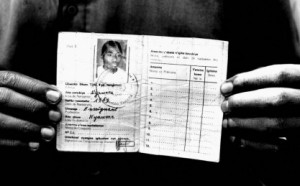

Europeans colonized Africa in the early 19th century and Rwanda fell under the rule of German East Africa. After World War I, Germany was no longer allowed to reside power over Rwanda, and in 1916 power and occupation was transferred to Belgium. The Belgians favored the Tutsis because of their cooperation and interest in wealth and nobility over cultural preservation. In 1933, mandatory ethnic ID cards were implemented and each citizen was required to carry it with them at all times. The ethnic ID card stated the persons name and indicated if they were either Tutsi or Hutu. With this system, the Tutsis were favored for jobs and education, and social mobility was impossible, citizens were forced to remain in the social class which they were born into. The implementation of the ethnic ID cards only caused more tension among the Tutsi and Hutu.

Prior to the the revolution, the Hutus were exploited for their farming work and punished harshly if they opposed the social order. They were second-class citizens to the Tutsi, and eventually the Belgians switch sides and began to support the Hutu majority rather than the Tutsi minority. After the second World War, more African countries that were still under European colonial rule pushed harder for liberation. In Rwanda, this liberation movement took its form in a full violent revolution. In 1959, the Hutus revolted and massacred then of thousands of Tutsis. This was a substantial loss of Tutsi people considering before the revolution, of the 2.6 people that populated the country, there were only about 300,000 Tutsi. Many Tutsi escaped to neighboring states such as the Congo, Uganda, Tanganyika, and Burundi. Hundreds of thousands of Rwandan Tutsis lived in exile on the border of Rwanda. They were not naturalized in any other country, and because they fled, were not allowed re-entry to Rwanda.

By 1961, the Hutus declared Rwanda a republic after forcing the Tutsi monarch into exile, and by 1962, after the UN passed a referendum, Belgium granted independence to Rwanda. There was now a majority rule and the Hutu dictatorship lasted through the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s and into the mid 90’s. Throughout this period, there was systematic political violence used against the Tutsis to maintain Hutu power.

Juvenal Habyarimana was the third president of the Republic of Rwanda

In 1973, there was another shift in the the Rwandan government by means of a military coup led by General Juvenal Habyarimana. Habyarimana formed a new political party called The National Revolutionary Movement for Development (NRMD). He was elected president and remained in power for the next two decades. Although Habyarimana was a moderate, discrimination and the persecution of Tutsis continued on through his time in power. Rwanda had become a corrupt one-party state and used foreign aid money for personal use and benefit. Habyarimana used this aid money to fill foreign accounts for his family and friends. Meanwhile, peasants and farmers were suffering through even worse poverty because of the collapse of coffee prices in 1989, hundreds of thousands of farmers lost their wages. The Rwandan government encouraged the farmers and peasants to blame the Tutsis for their hardships.

In 1990, the children of the Tutsi refugees desired to come back to Rwanda once and for all. They formed the RPF, Rwandan Patriotic Front, which invaded Rwanda from Uganda. For two years they fought a civil war against the Rwandan government, and in 1992, a ceasefire allowed the two groups to negotiate and in 1993, Habyarimana signed an agreement which would create a transition government that would include the RPF, and allow refugees to return to Rwanda. This sparked a quick and violent reaction from the Hutu extremists who despised the power sharing agreement.

On April 6, 1994, President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down over Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. This plane was also carrying the President of Burundi. Within the next hour, the Rwandan army and Hutu militia started to murder Tutsis and Hutus who were not extremists. Non-militant citizens were encouraged to take part in the massacring of Tutsis and within the next two weeks, the death toll reached around a quarter of a million people. A civil war began between the RPF and Hutus. 2 million Hutus fled Rwanda.

On July 18, the civil war was declared over and the new president was Pasteur Bizimungu. They established a new power position, vice president, and Paul Kagame took that position. Peace, however, did not make life in Rwanda much better. The civil war had drained Rwanda of all its money, and most schools, hospitals, police force, and offices were destroyed. Kigali, a once sprawling town of 300,000 now only had around 50,000 residents, although food and water were difficult to come by.

An estimated 100,000 children were separated from their families, orphaned, or abandoned, and around 300,000 children were killed in the genocide. Around 250,000 women were widowed, and the most widely accepted death toll is 800,000.

Sources:

“The Rwandan Patriotic Front (HRW Report – Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, March 1999).” The Rwandan Patriotic Front (HRW Report – Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, March 1999). The Human Rights Watch, 08 Aug. 2014. Web. Nov. 2014.

“Hutu Power Re-groups.” As Hundreds of Thousands Poured into Refugee Camps, in Kigali There Was Nothing but Debt. Rwandan Stories, n.d. Web. Nov. 2014.

“Rwanda.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Nov. 2014. Web. 30 Nov. 2014.

This is the default footer layout. You can easily add or remove columns in the footer.

This is the default footer layout. You can easily add or remove columns in the footer.

Recent Comments