Modern Art History – Dr Brantl

Pseudo Exhibition (Writing exercise)

4 Dec 2017

Transcendence and Reminiscence of Humanness

By Manuel Delano Pizarro

From times unknown, Humanity has been interested in the future, both in the legacy left for future generations and the possibility of an afterlife. This topic of transcending has been a very common theme through art history, since art is the clear representation of the cultures which produce it. Kant said there was a transcendental kind of relation to objects, where our cognition is occupied not with objects themselves, but with our way of understanding these objects, our a priori of the objects.[i] Transcendence is not, in this context, related to a godly or divine concept, but to the capacity to overcome-beyond the context of what something is part of -in this case, artistic objects.

Even if an artist wants to convey a specific meaning with an artwork, the context of the viewer will always influence the view this last one will have, and the understanding of the piece will be affected by it. The a priori relation with an art piece is more important, sometimes, than the posteriori knowledge one can have of said artwork, thus, changing the way one can understand and relate to the object. This is why it is so important -and especially to me as an artist- to be able to convey meaning in a way that is transcendental.

Once artists are not there to defend their artworks, their works have to be able to speak by themselves, they have to be able to show the words and thoughts of the artists who made them. Art is not only pretty objects on the wall or pedestals, it is not just a big monument in the middle of a piazza. Art is more than that; art is a statement of the life of an artist, of their context, of their culture. This is why art is so important for society, even if it has no direct functionality within society. Art does not save lives. Art does not help us travel long distances. Art does not (usually) make our economies bigger. Yet here it is, and it has always been. It is so important for the human experience that we cannot run away from it. Every culture has developed their own aesthetics and canons, and has merged with the ones of other cultures, sometimes through appropriation and sometimes through mutual understanding.

Historically, good art is transcendental, if not we would not know about its existence nowadays. Art has to be able to convey the views of an artists, convey the strings that pull their society, show the struggles, tensions, and achievements of their political and technological contexts. But it also has to be able to capture at least aspects of the very essence of human nature. Art that does not relate to our humanness is not worth remembering. It doesn’t matter if it is a landscape painting, as long as it relates somehow to our humanness in nature -say how humans relate to nature, or what we dream of it, or what astonishes us about nature. Good art has to speak to humans with reminiscence of humanity.

This exhibition has been thought from this perspective. It is a recompilation of works that portray a search for the transcendental, a compilation of works that speak by themselves, while reminding us about our humanness. The works presented deal with the transcendental related to their own context, and even if the exhibition becomes historical -since it tries to bring works from different cultures, time periods, and styles-, it also brings works which can coexist together from a visual dialogue. These works talk to each other both visually and conceptually through the concept of transcendence and human reminiscence.

As an artist that comes from philosophy and literature, it is very important to me to have an emphasis on the narrative aspect of my pieces. To hint stories, to open doors for interpretations while telling with a sign what that door opens to. To me, art has to be an effective way of communication, and this cannot be possible if a work is too open for the viewers’ interpretation. As an artist, I like to guide the viewer to a basic understanding of the piece -doesn’t matter if written or visual arts. This hint of storytelling, and the slight guidance to the viewers’ understanding are, to me, what gives that transcendental a priori relation to artworks, and this is what makes viewers come back to artistic objects. My works selected for this exhibition follow into this categorization and ideals. They represent to me the beginning for a search of the transcendental and humanness, and also of a more didactic kind of communication -yet still trying to stay somewhat abstract on the way representation is rendered and used. They are the starting point of the creation of my own visual language.

For this reason, different pieces have a sort of a priori description, and then each has also some external information about the piece -related to the context of production, the artist, etc. Every piece has to be understood from the concept of transcendence and human reminiscence, and also, they must be taken from their narrative emphasis -narrations of their historical contexts and narrations within the pieces. The exhibition itself culminate with my own work -starting from historically contextual works within the topic of transcendence and humanness, so the viewer can understand where do these works fall into.

- Adelyn, Ash Wednesday, Alex Soth. Chromogenic print. 2000.

This photograph manages to capture the feeling of melancholic hope, an aim for what is coming up next, a sense of wondering. On the center of the image there is a redhead woman, pale skin, and bright eyes. She looks like resting against a metallic gate or fence. She is wearing a floral dress, with mainly red and purple tones for the flowers and green for the leaves, and a dark, solid monotone background. She has the strap of her purse crossed from over the shoulder from left to right, and on her left shoulder there is a tattoo that matches de colors of the dress. She looks away from the camera, over her right. With her head slightly tilted to the back, and her eyes looking to the sky, like wondering. In the middle of her forehead there is a cross of gray ashes from the Christian tradition of Ash Wednesday. The look of her face gives a feeling of calmed waiting, a feeling of day dreaming, and the soft glow of her eyes show expectation, a wishing stare. Yet, the commissure of her mouth gives the feeling of remorse, of a sad reminder of a possible “rainy day” feeling. One cannot not relate her to a Baroque painting -the emotion of her face, the tilt of the head, the religious feeling of the subject, even the religious symbolism, the gates behind her, the gray background behind the gate, everything seems like taken from a dream inside a painting of the Baroque period.

Transcendence and humanness are linked tight together in this piece. The very human feeling of remorse, and the general feeling of penance of this photography are ways to relate the viewer to the artwork. In my work, it is crucial to find a way to convey this humanness to talk to the viewer and engage them, to tell them a story and make them buy into what the piece tries to tell them.

As explained by the artist, this photograph was taken after Mardi Gras in New Orleans, after he met the model, Adelyn, on the morning of Ash Wednesday, when she told him “just cigarette ashes”[ii] -referring to the cross on her forehead. It is possible to say, after all, that the look of her face may be influenced by a remorse after partying during the last day of Carnival, and waking up on the street on the beginning of Lent. So full of remorse and shame, that she could have blessed herself and asked for forgiveness making the cross sign on her forehead with cigarette ashes.

In this same sense, it is possible to relate the composition, the subject matter and the meaning behind the image to Baroque art. The term ‘Baroque’ comes from the Portuguese word Barrocco, which means rough imperfect pearl. Baroque, on the contrary of Renaissance, took a more pessimist way of portraying human nature as a duality, showing the good and the bad in and of us.[iii] Rembrandt’s portraits, for example, were meant to emphasize the value of the person, to embrace the figure, show the power, show the money, and show the status. They were made out of the careful study of classical works and visual language, and it becomes clear there is a connection in this matter between Soth and classic works like Rembrandt.[iv]

- Portrait of a Gentleman, Simon Vouet. Oil on canvas. 1620.

Following the Baroque-like portrait of the young lady, a subtle smile greets the viewer, and the eyes call for attention, as an invitation for a closer look. A young man sits on a wooden chair with red cover and gold ornaments, reclining his arm over the backrest, showing a leather glove, ornamented with intricate folds on the over-wrist area. The white shirt is also embellished with golden details, and the neck collar finds itself swirling with grace over his chest and shoulders. The black coat looks like a fancy material, probably velvet or some sort of pelt. And the relax attitude is the final statement of ownership and power of the subject, which stares at the viewer with familiarity, yet somewhat distant and empowered. And the empty glass is the final detail to bring back the humanness of the subject, to remind the viewer that, as Benjamin Franklin said hundreds of years after this work was produced, “in wine there is wisdom, in beer there is freedom, in water there is bacteria” -and every man may feel the need to calm the thirst.

Vouet was a painter which excelled in portraiture from very young, but his most know works nowadays are religious and mythical. The prolific artist managed to be commission at the age of 14 to pain “a portrait of a lady of quality” in England, and seven years later to portray the “Grand Seigneur” of the Turks in Constantinople.[v]

Vouet’s attention to details of the humanness of his subjects is what interests me the most. Everything is a hint to the personality and social status of his subjects, and there is no single part of the composition that hasn’t been thought from a representative perspective. The attitude of the man, the glove, the glass, the collar, everything is perfectly acompassed to show not just the image of a man, but his most inner essence, with the highs and lows: a man that has power, but that can also fall for the taste of wine; a man of wealth, and yet that can hold a compassioned look in his eyes. In my work I try to convey these little details as well, to hint to the viewer the dichotomies of human existence, which are, in the end, what make our lives interesting and transcendental.

- Statuette, Unknown Artist. Terracotta. Greek, 3rd Century BCE.

Little details tend to become insignificant next to bigger works. Now the spectator is presented to a motherly figure that lifts her dress as a greeting to the viewer. The small, still statue invites for a closer look and a homey dialogue. The relaxed dress folds over the figure, hinting anatomy more than showing it directly, giving a sense of demure, of a female host inviting to come in to hear a story.

The Tanagra figurines are small terracotta sculptures from 3rd Century BCE Greece. They were manufactured with different molds for different parts, which gave many variations to the hundreds of figures that have been discovered. They were originally coated with a white base layer, and then painted over with bright shades for their garments -reds, blues, pinks, violets, yellows and browns. Their skin was reddish or pinkish, as well as their lips, and their eyes where usually blue. Gilt and black were used for details.[vi] These are believed to have served funerary purposes, because of their appearance as decorations of vases in tombs.

These pieces were directly related to transcendence and humanness. Since they were used with funerary purposes, we cannot not relate them to their connection to human transcendence in the Greek afterlife. The primitiveness of the figure and their very ritualistic use is something that really catches my attention. I like my work to be related to ritualistic settings, to a feeling of togetherness which is only possible through rituals. I like to engage the viewer through a primitive feeling of pertinence to the work.

- El Guitarrista, Pablo Curatella Manes. Bronze with black patina. 1921-24.

From the stillness of the Greek figure to the modern pace of the 20th century. A small pedestal bronze sculpture showing different volumes and rhythms, creating a play of lines and shapes in space -like a distorted painting coming out and off the canvas, inhabiting the three dimensions of our world. The contrast between rounded and sharp lines and turns emphasizes the musicality of the piece, which is a fair representation of the subject matter: a folkloric guitarist playing passionately the sounds of tango or lambada. The expressive line that comes from the lower back, right over where the guitarist sits, and that goes all the way up to his head, which tilts towards the neck of the guitar, accentuates the contrapposto of the figure, a clear reminder of the artist’s will to hint classicism, Renaissance, and even the very “cubist-neoclassical” Picasso. The dark color of the sculpture reminds of the low-fire clay figures of some areas of Argentina and Chile, which usually have musicians as part as their motifs -especially guitarists. With both imageries combined, this piece becomes a clear call to attention of the Spanish side of the very South American Argentinian folklore, a search for identity and a search for reconciliation with both the European and the South American roots of the artist and his country.

Curatella studied in Europe with Bourdelle, and met different artists like Leger, Le Corbusier and Juan Gris. This last one was really influential for him. The cardboard figures -folded and articulated (movable)- of this artist gave Curatella the idea of how free sculpture could be and, thus, an opening to his new sculptural work. El Guitarrista is his first sculpture that announces his search for somewhat getting away from the baroque aspects of cubism, because he wanted to simplify the forms, being more intentionally geometric.[vii]

As a Chilean artist studying in the US, and with interests in classical European art and oriental art (especially Japanese), I find myself faced with the issues of interculturality. It is difficult to be able to convey parts of my own culture, and parts of the cultures and aesthetics I am fond of, while also talking to an audience from a third cultural context. This is why I like seeing the works of artists that face this same struggle, and be able to learn from them. And this work is a perfect example of this situation.

- Indian Canoe, Albert Bierstadt. Oil on panel. 1886.

Also touching the subject of interculturality, appears the painting of bright light and warm colors that create an atmosphere of calmness and contemplation, while a canoe sails on the still, reflective waters next to shore. The sun creates cast shadows that balance the light with deep contrasts, enhancing the reds of the sand, the rocks and the fall leaves of the trees. Nature encloses the canoer, showing the finiteness of being a human against the immenseness of nature, of existence itself. A human compared to a rock seems small, one person compared to the sands of the shore becomes lonely, a human compared to the huge trees -and then to the forest- becomes small, and compared to the sky humanity becomes even smaller. And yet, the sun illuminates all, warming the setting, giving light, giving color, giving life. And the stillness of existences keeps moving at a rate we cannot see, a rate we cannot imagine, we cannot comprehend.

Bierstadt engaged deeply with the spiritual and sensory tenets of German Romanticism when he studied at Düsseldorf Academy of Arts. This is how he got interested in emphasizing the sublime or transcendental experience through his painting, which perfectly suited depicting the American West of his time. His aim to convey a sense of the divine through nature is strongly rendered in this painting, where a lone Native American navigates the waters on a canoe, with a majestic sunset behind.[viii] Bierstadt romanticized landscapes of the West, and painted generally on a large scale with great detail -as expected from a good romantic painter-, this captured the attention of 19th century art collector, and he found a prolife niche to become successful and recognized not only in the US, but internationally. His beautiful and enormous paintings found their way into private and public collections at very high prices. Later on, the new interest in Impressionism turned public taste away from his highly detailed, romantic work.[ix]

The use of light, of color, is something I am very interested in, yet haven’t explored as much. Since most of my work is three-dimensional, I still need to figure out ways of getting this same emphasis of light and color without relying on constant, controlled external lighting. I am really interested, as well, in developing this sense of human finiteness in my own work, and I find it a challenge to do so in pedestal works. This piece reminds me of my aim for a further development in more monumental work, or at least to come off the pedestal and the wall. I want to be able to render atmospheres, to bring the viewer into a setting, a stage created for their own experience.

- Quipus 58 B, Jorge Eielson. Canvas and acrylic on wood. 1966-68.

Contrasting with the bright colors and traditional rendering of the visual poetry of Romanticism, the viewer is presented to a work with no lose ends. “Nudos que no son nudos y nudos que solo son nudos.” The tensions from the knot of a white canvas to where it grabs the panel which supports the cloth drags the eyes from one corner of the piece to the other. The cast shadows give rhythm and organization, while also giving a feeling of contained chaos and struggle. The darker panel mutes the piece and brings the canvas away from the viewer, which is compelled to get closer and examine the piece from up close.

How many times we give importance to things that are not important, and how many times we do not think of the importance of very important things? Rhetorical or not, this question is difficult to respond to, since we do not remember things we don’t consider important, and exaggerate things that we believe to be important. We erase from our memories what we do not want to see, and see only what we want to see. Same as it happened with the Spanish in the Conquista period, we try to erase so many important things from our context, from our society, from our day-a-day lives, and we do not appreciate the essence of what is important and meaningful because we don’t see the value of some things that can be of a great matter.

Eielson’s Quipus (Incan word for “knots”) represent a language built on the use of variations of a single motif, the knot. The artist took the name from a traditional encoding system of the Incas, used to collect data and keep track of values on different knotted strings, where each type of knot, string used, distance, and combinations have specific meanings. The quipus disappeared with the Spanish conquest, but maintained their status as a historical symbol. Eielson’s work has used the concept of quipus to develop his own visual language, every chromatic surface, with each color, twist and intersection concretizing a symbol or word. After all, Eielson is both a visual and literary artist, and the word, language, and coding are really important for him and his work.[x]

Coming from literature and philosophy, I am very “fond of the word.” My work is always related to big philosophical concepts, to concepts of the human experience, of narratives, poetry, etc. I am still developing my own visual language to convey this personal interest in coding, linguistics, and conceptuality, while also trying to follow my passion for classical canons and tradition. I believe this work by Eielson is a perfect example of this same search for coding systems by other artists, and it is one of my influences to find a personal visual language to talk to the viewer.

- Head of a Dancer: Harald Kreutzberg, Richmond Barthé. Bronze. 1933.

The balance and contrasting forms of the quipus can be seen in contrast to the representative bronze head of a dancer. Like floating over a cubic pedestal, the head of a man stands still. This bust-like sculpture has a feeling of post mortem masks and the heavy shadows accentuate this ominous feeling of starting to the image of the face of a dead person. The cubic pedestal grounds the figure of the head, while the slight frontal tilt of the head makes it look like if it was going to move on any moment. This tension between stillness and movement creates a feeling of stopped motion, like the photograph of a dancer in the middle of performance, a frozen moment in time and a face of Zen-like concentration before the lounge into a series of pirouettes to give everything on stage, all what the dancer is given in the performance to an audience that might not even remember. An all or nothing situation, and the dancer gives it all.

Barthé was really interested in human subjects, in portraying their innermost essence, their humanity. He was also very fond of dance and theater, and he produced a body of work about this subject, portraying the essence of dancers and their human experience irrespective of their race or sex. He even studied dance with Martha Graham, which gave him a better understanding of dance techniques, movements and human form.[xi]

Again, the use of codes comes to the surface, but instead of a very enclosed coding -like Quipus 58 B- this time it comes from a very representational perspective. The very anatomically accurate piece of Barthé manages to portray a story of the subject while showing his human essence. The dancer seems to be concentrated to perform, entering into a Zen-like state of mind, and the contrast of colors and forms between the pedestal and the head create an emphasis on the face which does not let the eye move away from it. This kind of precise rendering is what I try to aim for when I work in a more representative piece, yet I still need to mix it with an ongoing developing visual language of my own.

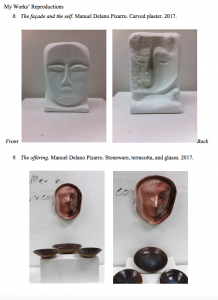

- The façade and the self. Manuel Delano Pizarro. Carved plaster. 2017.

Continuing with faces on pedestals, the viewer is presented with a white mask-like sculpture. The concept behind it is the dichotomy between the façade we show to the world –the “put-together” of us- and the internal, essential duality of our “real selves.” On the outside, the lines are more or less polished, rounded, aiming for elegance –yet not perfection (humans are not perfect). The inside has two sides to it, the left mechanical one, and the right “blank”, open one (like a white canvas). Those two sides represent the logical left and artistic right. It becomes somewhat notorious the influence of imagery of theater masks, both on the front façade and the back, internal dual mask -which come directly related from my own interest and background in theater. This sculpture is an aim for representation of the human duality as social characters and as private beings. One cannot enter the mind of a person, and can only see what is shown by their display, their construction of a character that performs in the day-a-day life. Our transcendental selves cannot be seen until we break that façade and open to other people, and yet we tend to keep this part of our humanness locked away from the eyes of society.

- The offering. Manuel Delano Pizarro. Stoneware, terracotta, and glazes. 2017.

Now the face gets transferred to the wall when a reddish mask hangs from it. In front of the mask there are three bowls, two small ones and another one slightly bigger, the three of them resting on a pedestal. The religious imagery comes to play. A feeling of ominous presence is imminent, and the viewer feels the aura of a sacred ritual that may have taken place -or is at that moment. The altar-like piece reminds of pagan rituals of offering to idols, and the red colors of the different pieces feels sanguine and primitive. The human hand seems to be closely related, and yet cannot be seen in the work, almost like if it has appeared to be worshiped. Transcendence and humanness get tied together in this piece, and it also encourages the viewer to become a part of it with the ritualistic aspect of the piece. It is a sort of quote to the archetypical ritual, to the pagan culture and the obscure story of western culture, which has always been present in the undertones of society and as a cultural background that has been systematically hidden from the official history and tradition since the Catholic Church overcame the pagan culture.

_________________

[i] Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated Guyer and Allen W. Wood, Cambridge University Press, 1998. p. 149. PDF. 24 Nov 2017.

[ii] “Ash Wednesday, New Orleans photobook by Alec Soth.” Photobookstore, Photo Editions Ltd, 2017. Web. 25 Nov 2017.

[iii] Charles, Victoria, and Klaus Carl. Baroque Art. New York: Parkstone International, 2012. p. 7. PDF. 25 Nov 2017.

[iv] Fuchs, Rudi. Dutch Painting. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Print.

[v] Simon Vouet, “Portrait of a Gentleman,” Blanton Museum of Art Colletions. Univerity of Texas. Edb. 26 Nov 2017.

[vi] “Tanagra Figurine.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britanniva, inc., 22 Aug, 2013. Web. 26 Nov 2017.

[vii] “Pablo Curatella Manes.” Obra de Pablo Curatella Manes, Lambda Produccion, 2014. Web. 25 NOV 2017.

[viii] Albert Bierstadt, “Indian Canoe,” Blanton Museum of Art Collections. University of Texas. Web. 26 Nov 2017.

[ix] “Biography of Albert Bierstadt.” Albert Bierstadt – The complete Works – Biography, Albert Bierstadt Org, 2017. Web. 26 Nov 2017.

[x] “Jorge Eielson October 14 – November 16, 2016, Gallery 2.” Ed. Justin Conner, Jorge Eielson Exhibition – Andrea Rosen Gallery, Andre Rosen Gallery, 2016. Web. 26 Nov 2017.

[xi] “Richmond Barthé – Head of a Dancer (Harold Kreutzberg).” Narratives: Head of Dancer, Richmond Barthé, Univeristy of Meryland Art Gallery. Web. 26 Nov 2017.