Rethinking What It Means to be a Christian

Each Sunday a group of around 60 or 70 people from many different backgrounds arrive at Journey Imperfect Faith Community with a blank slate, at least that’s the idea. The North Austin church appears no different than the Baptist, Presbyterian, and Lutheran churches in its vicinity given its angular roof and the shape of a cross on the front of the building. However, upon entering Journey and seeing the mismatched chairs and couches arranged in no particular way, one may no longer feel as if they’re in what Rick Diamond, pastor and founder of Journey, calls “Church Row.”

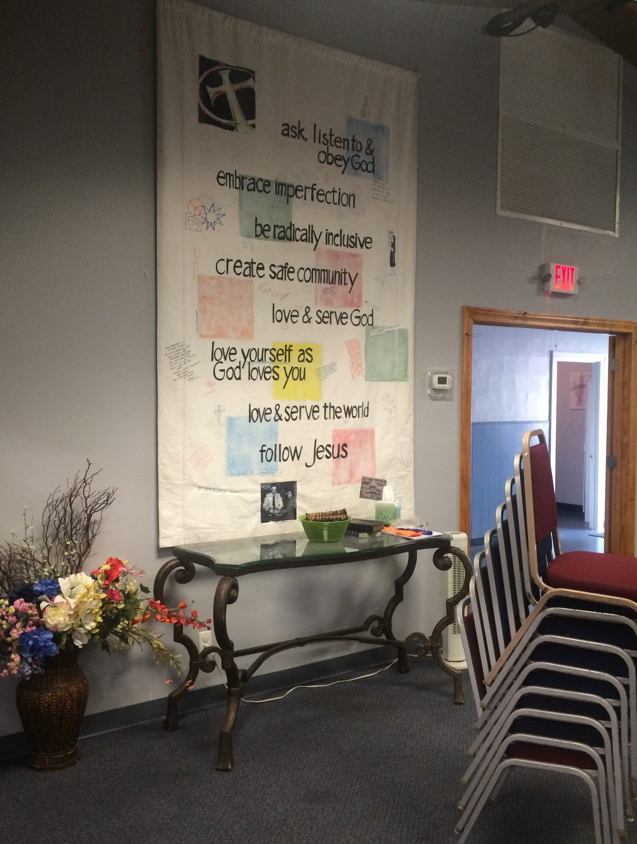

There is no set creed at Journey. Instead, a banner hangs on a wall that paraphrases the only scriptures they reinforce. The two that Diamond believes are easier said than done are ‘embrace imperfection’ and ‘be radically inclusive.’

Rather than distributing worship bulletins, Journey has a worship series with a theme that changes each month. One theme was about the feelings, fears, and anxieties people may have about money. The service began with a trove of treasure in the center of the room made by a member of Journey.

“We talked about how God couldn’t possibly care about how much money you have,” Diamond said. “Or he could have a beautiful banquet laid out for us and it might go unnoticed because we’re so caught up in worrying.”

The service begins at “11ish” in the morning with a child ringing a bell that someone found in an old firehouse, which moves around the room depending on the props needed for the theme.

“It’s a way of saying kids are important and worship is starting so everyone should shut up,” Diamond said.

He recently met with a group of Methodist pastors from east Texas and south Arkansas that come from traditional settings but want to help the context of their ministries evolve. However, he saw that sometimes territory and custodianship resists change and sees it as a threat.

Diamond was a Methodist minister for six years. “I loved the people and making a connection through teaching,” he said. “But there was also a part of me that really hated it because a bunch of it was about having committee meetings and deciding the rules for the playground. And I didn’t really give a shit about stuff like that.”

Sabrina Piper-Owens, a “Journey-er” as the church-goers call each other, has similar feelings about the more “mainstream” forms of worship. Having grown up in a family with a strong ministry background, she ended up working for the Baptist church she grew up in, which was located across the street from her childhood home. She was mainly interested in the postmodern services offered there, but then got moved to mainstream services. It was then that she decided to take a break from ministry.

“It wrecked me. It wasn’t what I expected,” she said. “It didn’t resonate with my faith or experience and I got lost in it.”

After completing a Doctor of Ministry degree in Postmodern Church Leadership from Drew University in 2001, Diamond moved from New Jersey to Austin to work at Riverbend, a mega-church. Although Diamond valued coming together for a service, he felt that something was missing. For him, there wasn’t enough emphasis on how to reach out to the “messy, weird world that is the 21st century.” Three years later, Diamond left.

Almost immediately after his departure, many people from Riverbend that were also interested in a more pliable expression of worship contacted him.

“I just wanted to go sit under a rock and they told me, ‘well we rented out the YMCA off McNeil Road on Sunday so maybe we should all just go there and see what happens,’” Diamond said.

A few months later, some of the people that came from Riverbend got the idea that neither Rick nor his wife, who also helped out at the ground level, were interested in starting another mega-church with him as the talking head instead of someone else. They ended up leaving and taking their money. But many other people that were interested in experimental worship joined because for them, Journey was a good fit.

John Corbin and his wife Susan, are one of the families that have been with Journey since the beginning. Although he was raised in a Southern Baptist church, John took a break from attending church once he moved to Austin for college. This wasn’t because he was “particularly traumatized by it,” rather he just didn’t get anything out of it. This break ended up being around twenty years, until he began attending Riverbend. Susan was more engaged in Riverbend than John, but they both thought it would be best to start going to church again once they had kids.

Kenny Wood, a former pastor there, was instrumental in easing Corbin back into the swing of things.

“Kenny was more spiritual than religious. He defined religion in his own terms and didn’t follow anyone else’s cookbook,” he said.

Corbin also admired Diamond’s way of communicating. When he and Susan found out Diamond would be leaving Riverbend to start his own church, they were ecstatic. However, it wasn’t long until many others who followed Diamond began losing the “new toy luster” as Corbin called it.

“People soon learned that Journey wasn’t like Riverbend. We weren’t walking into a beautiful multi-million dollar building to watch a show,” he said. “We needed help with everything from accounting to cleaning to buying paperclips. It’s a heck of a lot of work and a lot of people weren’t built for that, so they left.”

Diamond refrains from keeping a count on exactly how many people have become a part of Journey because he believes that counting just turns them into numbers. This has led to criticism from other pastors because they wonder how else one measures their effectiveness in spreading the word of God.

“People are attracted to the idea that whether you’re screwed up or wonderful or both, you’re welcome to come as you are,” Diamond said. “We’re not going to count you, get you to spend more money, or be something you’re not.”

Journey has been around for 12 years now. For the most part, people hear about it through word of mouth and when they’re in search for an LGBTQ or postmodern church. Some come with their own tradition and experience with religion. Others come after having bad experiences with a church or none at all.

For Piper-Owens, the way she felt about her old church in contrast to the way she feels about Journey came full circle through an unlikely celebrity: Britney Spears. While directing the mainstream ministry services, her former pastor brought up Spears and talked about how unfortunate it was that people are running around shaving their heads and setting bad examples for kids.

“It was a small thing but I thought, if Britney Spears were here right now, she would not feel welcomed in our space,” she said. “That means we’re creating an unsafe space for others.”

A few weeks ago during a bible study at Journey, Diamond brought up the concept of scapegoats and mentioned Britney Spears. He talked about how there are kids that become trained to be entertainers and sent out into a world that isn’t completely sane and people still tear them down.

“It was a bittersweet, heartbreaking, and beautiful thing to feel like this hole in my heart had been filled,” she said.

On thing that is frequently in the speech of Diamond and fellow Journey-ers is “the thing.” It varies from person to person, but the general message emphasizes inclusivity.

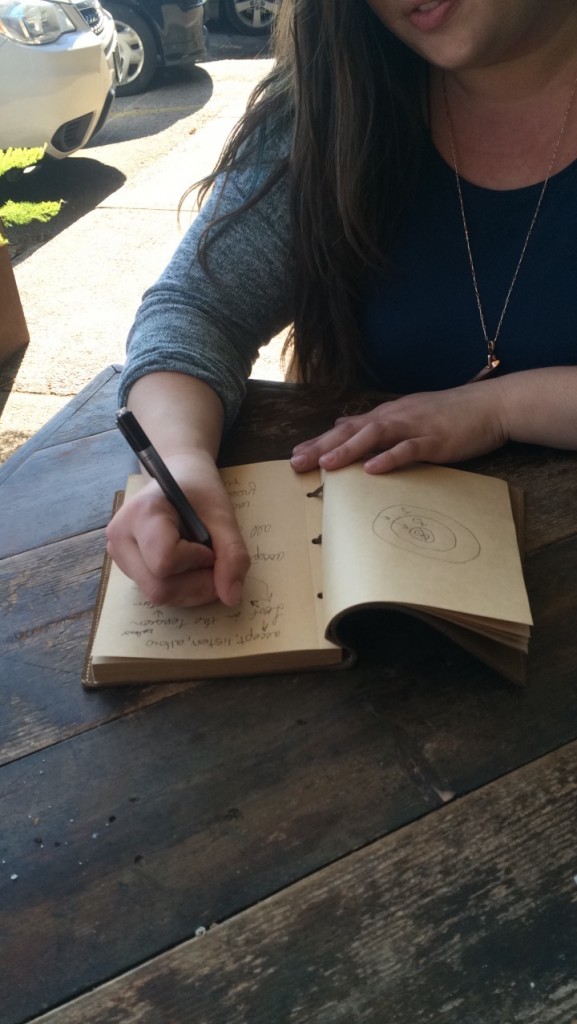

When asked her thoughts about what exactly “the thing” means, Piper-Owens is pensive. Finally, she takes out a notebook Diamond’s wife bought her for graduation, and jots down several words before answering.

“We talk about how love isn’t a feeling, it’s an action. When we love intentionally, we are being vulnerable and giving others the space to be vulnerable,” she said. “Once we do that with people we already have relationships with, we must do that with other people we might not be comfortable with.”

For Diamond, part of the joy of ministry is to remember that every single person is God’s favorite person “even if they drive him crazy.” But it’s okay, he said. Because he’s the thing that drives someone else crazy. The trick is to be in a community with people that are loving and caring but also honest, because it’s risky to be open with each other.

“Journey is sticky,” said Corbin. “Some people have gone years without going, then one day they show up and they’re regulars again. For others, it has to do with what phase they’re at in their life. Some come to Journey to grow, then things change and they’re able to go out on their own. And we always wish them well.”

Leave a Reply