Post by Natalie Mulin and Daniel Collins

For our trip to the Water Quality Protection Lands, we visited a variety of lands around the Edwards Plateau, each contributing to water diffusion into the aquifer in some way. We met our guide, Kevin Thuesen, at the LBJ Wildflower Center and then we traveled around together to the various sites that he manages. The first spot was a pretty hefty acreage of land located in the Onion Creek Watershed (about 15 miles Southwest of Austin). Here, Kevin relayed to us how the land was purchased through a process called Simple Acquisition. Much like it sounds, it is the process by which private land is purchased from citizens and incorporated in the protected lands. Kevin stressed that in order to obtain proper water quality, the lands must be managed with the care that limits impervious cover and pervasive invasive species.

The other method of acquiring protection land is through Conservation Easements, in which Private Landowners partner with landowners to ensure the land is held to WQPL standards. The WQPL currently protects 28,358 acres,62% of which are easement owners.

Conservation easements are basically agreements where landowners sell their development rights to someone while still keeping ownership of their land. This makes it easier for the Water Quality Protection Lands to moderate and regulate private lands over the aquifer while not making landowners give up their lands completely, which frankly would never happen. It’s an extremely innovative and effective way to manage land on the recharge zones. Landowners have to abide by regulations concerning the number of cattle they can have, the amount of impervious coverage they can build, what pesticides they may use, and a few others. On the easement properties, the WQPL can visit and assess how landowners are treating their properties in sensitive ecosystems.

Kevin used a great example when explaining how they ensure the quality of the lands. He referenced two adjacent fields. One with a high biomass of Juniper and other trees while the other consisted of mainly prairie. The prairie field, as Kevin put it, and many like it were maintained by indigenous groups for centuries through using prescribed burns. Today, in order to limit the presence of invasive and enrich soil quality, the WQPL engages in prescribed burns on all of their acquisitions every 3-5 years (or more depending on the are), also offering prescribed burns to easement owners.

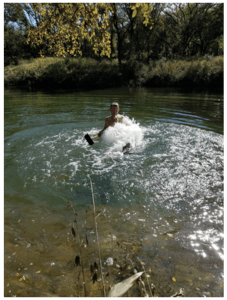

From here we witnessed Kevin actually unclogging a vent that led to a cave system flowing directly to Barton Springs. Sporting his swim trunks, sun hat, glasses, and hoe; Kevin plunged into the tributary and began raking sediment from the vent. Not long after, the new influx of water sent a geyser spewing forth from below! Dozens of other bubbles began trickling from the banks of the river, revealing a plethora of diffusion sites along the river. Kevin explained this was caused by oxygen being pushed out from below as more water pushed forth.

One of the caves that feeds into the aquifers. People used to throw dead goats in these caves 🙁

Very recently, people in the communities surrounding this particular cave wanted to dump gasoline into the cave to kill the rattlesnakes in their neighborhood… a really bad look!

Above is a project conducted by the Water Quality Protection Lands to track how much water enters the cave below and eventually feed into the aquifer. The project was a response to a proposal by TxDOT to develop on land directly on top of a recharge zone over the aquifer. TxDOT insisted that only a few acres would be needed for drainage into the aquifer, but observations by WQPL suggested much more land would be needed Their measurements showed that closer to 60 acres of water recharged directly into the cave. We noticed there were cameras around the site and asked Kevin why he would need cameras for the project. Apparently, someone had disrupted the study and destroyed some of the weirs very strategically. Kevin explained that the only parts of the equipment harmed were the parts used for measuring water, everything else was untouched. He didn’t expand on who did it or why, but it certainly made us wonder…

Leave a Reply