Where we are so far:

So far, we’ve traced the chain of events which have led to and through the 2006 War on Drugs declared by the Mexican government. So where are we now?

Statistics for the years after 2013 are controversial, due to the long delay needed to perform accurate statistical analysis of the data, but from 2006-2013:

26,121 unsolved cases of disappearance

over 60,000 confirmed cases of organized crime related murder

likely over 100,000 organized crime and drug-related murders (considering many cases might be misdiagnosed due to not meeting the strict evidentiary-burden to be classified as an organized crime related murder.)

Just Some Discretionary Public Violence and Threats, 2006-2012:

Intimidation of Judicial Officials

Intimidation of Law Enforcement

Intimidation of Public Officials

Active counterintelligence and infiltration operations to uncover personally identifiable information on government officials

“The Balaclava Index” of near-failed states. Who’s wearing the masks?

Torture without murder

Snuff films featuring the torture, and murder and then distributed to the family of the victim

Mass Executions

Beheading Executions (later using chainsaws)

Execution by Necklacing (taken from Apartheid practice)

Kidnapping and disappearance of Children, Women

Enforced Protection Rackets

Frequent Direct Attacks on Police Offices/Convoys

Daylight raid, murder, and arson of a Monterrey casino

Hanging and Placement of bodies and heads in town squares and on major thoroughfares

Large-scale theft and return of Mexican police vehicles to send a message

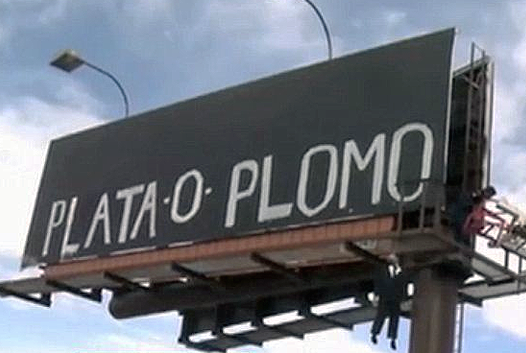

Illegal posting of threatening messages on billboards

The common intentional kidnapping of rival cartel members instead of much easier and less risky murder:

The Terror-Crime Continuum:

So what’s the difference between a terrorist and a violent criminal?

Literally nothing if you leave it at that. A terrorist is a violent criminal.

Traditionally, a terrorist is a criminal who uses violence or the threat of violence specifically to externalize an effect of a crime onto a larger population for an ideological goal.

Most violent criminals are motivated by passion or profit, and don’t desire to externalize the effects of their crimes on the public at large, indeed, usually they attempt to conceal them.

While a drug cartel might not fit the traditional definition of a terrorist organization, it can certainly use acts of terrorism, such as those used in Mexico for the purposes of externalizing the effect of its crime onto larger organizations, groups, and vast swaths of territory.

Let’s compare some terrorist organizations with the Italian Mafia:

Consider the grand ambitions of politically and religiously minded terror groups such as factions of the

FARC,

Shining Path,

the Japanese Red Army,

Action Directe (+7 similar leftist groups in Western Europe),

the Muslim Brotherhood,

Lashkar-e-Taiba,

DAESH,

Haganah,

and Al-Qaeda…

…who all launched terrorist campaigns geared toward the expansion of a political power which would directly serve a tangible benefit to themselves.

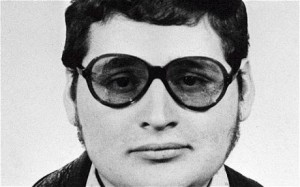

Carlos “The Jackal” Left-wing Terrorist for hire

While one cannot fairly question the motivations of the independent participants of terror campaigns, the broader vocabulary of revolution is that of one power replacing another, one system replacing another, and the arbiters of the new system are more often than not, the revolutionaries which have used the tactics of terror and violence to get there.

When looking at terror enterprises in such light, it is not difficult to see how some traditional criminal enterprises could easily be defined as terrorist in nature:

Elements of the Colombian drug cartels funded, either in currency or cocoa, the terrorist campaigns of the FARC resistance in Columbia.

The Cosa Nostra, or Sicilian Mafia had hands in illegal prostitution, gambling, smuggling, protection, and public service rackets, as well as violent feuds in Italy during the twentieth century. Additionally, the Mafia was involved in vote rigging and a widespread public and judicial intimidation campaign to control government and law enforcement efforts to disrupt their enterprise.

While the Mafia was not ultimately ideologically motivated to change the political system in Italy, they were historically founded on a feudal system of close family ties and distrustful of government intervention, which ultimately culminated in the rise and fall of Mussolini. In such an environment, Cosa Nostra’s violent but business-minded antiestablishmentarianism was not far departed from more ideologically-minded terror organizations who sought a change or loosening on perceived government authoritarianism.

La Cosa Nostra

Think about it like this:

Kidnapping and/or murder often use initial acts of violence, or the threat thereof to perpetrate the eventual crime. In either case, the crime is meant to internalize the effect upon the victim and/or those close to them.

Now consider kidnapping/murder and/or torture committed for the sake of externalizing the effect of that crime onto a much broader collection of people. This is what we’ll call terrorism for our purposes.

One the continuum of criminality, terrorism is often just a matter of perspective.

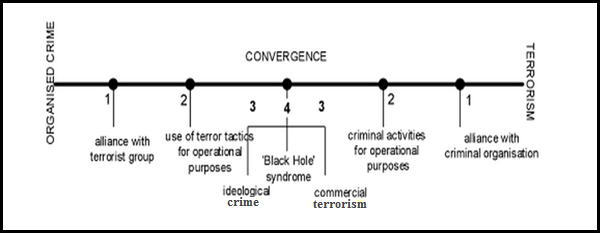

Consider the crime-terror continuum, first penned by Tamara Makarenko:

http://www.iracm.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/makarenko-global-crime-5399.pdf

As you can see above, outlines the tendency of a single group or entity, whether it be ideologically or tangibly motivated, to slip up and down the scale depending primarily on the environment in which it operates as well as on the internal dynamics and individual motivations of actors within the organization.

Terror groups are on one side of the continuum and criminal organizations are on the other; different operational requirements bring them closer to center, at which point they are hard to distinguish between the two, an area Makarenko defines as the ‘Black Hole’.

In the land of the blind…

So why does a business enterprise become a organization that uses terrorism? Because it’s criminal. It exists outside of legal protection and recourse.

Laws exist in a society so as to protect:

individual rights,

property rights, and

contractual obligations.

Anyone who betrays their duty to honor these rights will be forced to internalize the costs which they externalized onto others and onto society as a whole by damaging the trust, therefore value of rule-of-law in general.

http://www.iep.utm.edu/law-econ/

The point is to maximize the efficiency of society by normalizing the behavior and providing acceptable recourse and effective remedy for a stable society and economy.

…the one-eyed man can aim.

Any illicit or criminal entity forfeits its claim to protection within the law, which means it must provide its own.

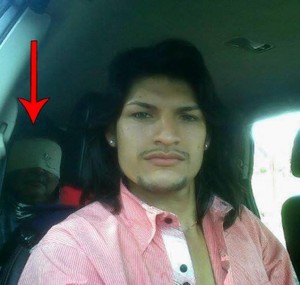

Knights Templar enforcer ‘Broly’ posting to Instagram with victim

And of course, as the government is no longer there to enforce a cartel’s rights or agreements by force, the cartel must create its own force.

Same victim found days later

The Burgeoning Chaos

Armed cartels are prone to disagree about one another’s rights in the competitive, unregulated market of the drug trade. On top of that, the government poses a constant existential treat to daily operations, profits, and to the cartel itself.

The Nash equilibrium shows how two independent actors, without complete information about the other’s decision to either cooperate or defect against them, are each faced with the most rational decision for themselves being the one which provides the most systemically inefficient result. Despite knowing that the best outcome is for both to cooperate, the best choice each individual has is to defect on the other, which provides benefits in addition to mitigating the cost of being defected on. Laws provide a way of mitigating this effect by ensuring a certain level of informational symmetry and by disincentivizing defection.

What this means to a drug cartel is that, without a government to ensure cooperation, any cartel is more likely to compete and combat the other, which will escalate the scale and often the severity of the violence. In economics, this is sometimes called “the logical trap of standalone rationality.”

What follows is the escalating costs of cycles of violence and arms races.

Note: I’ve avoided displaying small-arms such as pistols, rifles, and sub-machine guns because it’s simply impossible to express the scope and sheer volume of guns moving throughout Mexico, though you are more than invited to google results of your own. What follows is just a sampling of the results of the arms race:

Modern frag grenades and belt-fed M-19 automatic 40-mm grenade rounds.

RPG-7 launchers and .50-cal sniper rifles

Assault light machine gun, Barrett, and Minigun.

Captured ‘Narcotank’

Terror is Good for Business

“Kill one man, terrorize one thousand.”

-Chinese Proverb

This method of violent competition is very costly and inefficient. A more efficient way to operate, given a certain level of lawlessness, is to commit act of violence, the effect of which, will be externalized to a much greater population or area of people.

This is the compounding effect of fear and the beginning of the use of terror as an alternate method of control to the constant application of force.

The best way to follow the living history of the Mexican drug war as it evolved is with the LA Times’ Mexico Under Siege compiled coverage of special reports going back to 2008. http://www.latimes.com/world/drug-war/

The efficiency effect of terror (in addition to probable corruption) on a Mexican prison guard force during an organized Los Zetas jail break.

End Game

As the cartels use the tactics of terror on each other, the government, and the population, there is a tendency for some cartels and organizations to merge or take over a smaller organization in order to monopolize an area or trade route. Often, this is counterbalanced as the larger organization will leave create incentive for smaller operations to wither splinter off the larger one, or to simply form to take advantage of the economies of scale advantage left in the smaller and local markets.

There are three clear outcomes of this constant churning effect within Cartels, each listed with their actual occurrence since 2012:

1. The government wins some significant victories. It’s unlikely that this will lead to a major change in the climate of the Mexican drug war, but there would likely be at least a temporary downturn in violence after such decapitation events.

One of many recent cartel-boss arrests

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/05/mexico-drug-kingpins-behind-bars-violence-corruption-unchecked

2. Chaos reigns as smaller and smaller violent entities fight in ever more complex cycles of violence and retribution.

Los Mata Zeta “The Zeta Killers” Vigilante group or proxy warriors?

Diana, Hunter of Bus Drivers

http://www.thisamericanlife.org/diana-hunter-of-bus-drivers/

3. Victorious cartels move from an insurgent-terror campaign into the role of proxy authority and a stability-inducing, counterinsurgency-style role. This is due to being a more efficient way to hold a territory once it is largely secured. This role uses soft power and a hearts-and-mind campaign to supplement its underlying hard power, engender local loyalties, become a part of the local culture/identity, and to control undisputed territory.

Gulf Cartel Social Media Campaign

Follow up article:

http://www.dailynews.com/general-news/20130924/mexico-drug-cartels-helping-with-storm-relief

More Narco Corridos, just for fun:

“El Parton” – Columbian Narco Corrido about Pablo Escobar. A good example of the genre.

Additional Sources:

Miroff, Nick; Booth, William (26 November 2011). “Mexico’s drug war is at a stalemate as Calderon’s presidency ends”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/calderon-finishes-his-six-year-drug-war-at-stalemate/2012/11/26/82c90a94-31eb-11e2-92f0-496af208bf23_story_1.html

Makarenko, T. (2004). “The Crime-Terror Continuum: Tracing the Interplay between Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism”. Global crime, 6(1): 3; 130. http://www.iracm.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/makarenko-global-crime-5399.pdf

Gambetta, Diego (1993). The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection. Princeton University Press: 75-101. http://books.google.be/books?id=y3bv3tqWftYC&printsec=frontcover&hl=nl&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

“Italian Organized Crime”. Federal Bureau of Investigation: Organized Crime Database (2015). Overview of Italian Organized Crime and La Cosa Nostra specifically. http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/organizedcrime/italian_mafia

Wilkinson, Tracy, et. al. “Mexico Under Siege”. Los Angeles Times. Compiled coverage on Mexican drug war (2006-2015). http://www.latimes.com/world/drug-war/

Murphy, Helen; Acosta, Luis Jaime (22 April 2013). “FARC controls 60 percent of drug trade – Colombia’s police chief”. Reuters. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/04/22/uk-colombia-rebels-police-idUKBRE93L18Y20130422

Cole, Daniel H.; Grossman, Peter Z. Principles of Law and Economics, 2nd. Ed. Published by Kluwer Law and Business, NY, NY (2011): 32, 87.

Baird, Douglas, et al. “Game Theory and the Law”. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1994): 10, 40. http://www.benegg.net/courses/rct2/Baird_chapter_1.pdf

Truckman, Jo (5 March 2015). “Mexico drug kingpins behind bars but violence and corruption go unchecked”. The Guardian. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7a1-HXBCAU

Amanpour, Cristiane; Bello, Navarro (14 October 2011). “The most dangerous cartel on Earth”. CNN: Around the World. Video reporting/interview. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7a1-HXBCAU

Herrera, Yuri (4 October 2013) “Diana, Hunter of Bus Drivers”. This American Life. Mixed media: audio and text publication. http://www.thisamericanlife.org/diana-hunter-of-bus-drivers/