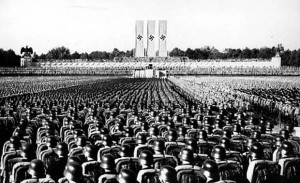

Fade in: A plane soaring through the mist of scattered clouds. There is an utter calmness in the air, which is soon to be dramatically broken. The ground below comes into view: Nuremberg. Thousands of heads look to the sky. The plane lands, door opens, Hitler appears. Cue deafening sounds from the astonishing crowds.

This is what you will experience in the first minutes of Leni Riefenstahl’s

Triumph of the Will (Triumph des Willens).

Riefenstahl was one who changed the face of documentary film forever. Her use of physical gaps and hierarchical distinction between leader and followers are just two of the aspects of the film that set it apart from other documentaries of the time. Triumph of the Will (1935) was monumental in that it was one of the first observational documentaries. It shows events – parades, mass assemblies, images of Hitler, speeches – that are occurring as if the camera was recording what would have happened…regardless if there were cameras present or not. There is no spoken commentary, only speeches by Hitler and other Nazi leaders, and this is how it differs from propaganda and documentary film. Triumph of the Will “demonstrates the power of the image to represent the historical world at the same moment as it participates in the construction of the historical world itself” (Nichols 178).

Riefenstahl was one who changed the face of documentary film forever. Her use of physical gaps and hierarchical distinction between leader and followers are just two of the aspects of the film that set it apart from other documentaries of the time. Triumph of the Will (1935) was monumental in that it was one of the first observational documentaries. It shows events – parades, mass assemblies, images of Hitler, speeches – that are occurring as if the camera was recording what would have happened…regardless if there were cameras present or not. There is no spoken commentary, only speeches by Hitler and other Nazi leaders, and this is how it differs from propaganda and documentary film. Triumph of the Will “demonstrates the power of the image to represent the historical world at the same moment as it participates in the construction of the historical world itself” (Nichols 178).

Riefenstahl was admired by Hitler, and in 1934, she received a call from Adolf Hitler himself and was asked to make a film of the annual rally of the National Socialist German Workers party (the Nazi party) – the largest-ever staged-announcement and demonstration, to all the world, of German rebirth (Barnouw 101). Hitler insisted it must be Riefenstahl. She agreed on the condition that no one, not even Hitler, would interfere with or even see the film until it was finished.

The film’s impact is said to derive from Riefenstahl’s choreography of images and sounds…

the marching of men,

the waving of banners,

the uniforms,

the swastikas,

the overwhelming cheers,

and smiling children at the front of the crowds, sparkles in their eyes as if it was Santa they were seeing.

Some other techniques that set Riefenstahl and her film apart from others are her unique camera movements and locations. She had thirty cameras in operation in order to make the film. Special bridges, towers, and ramps were built by the city of Nuremberg solely for the production of this film. Dollies were built to move along with marching troops, fire trucks were used to get unique shots of monuments throughout the city, and there was even a 120-foot flagpole that had been outfitted with an electric elevator in order to get wide shots from a bird’s eye view.

At one point in the film, during the powerful entrance of the three Nazi leaders, Riefenstahl shifts to a different angle, one that places the three men in closer proximity to the masses [of soldiers] while still continuing a vivid, purposeful sense of physical distance and hierarchical distinction (Nichols 96). There is also the brilliant contrast between the masses in the crowds…and one person, Hitler.

At one point in the film, during the powerful entrance of the three Nazi leaders, Riefenstahl shifts to a different angle, one that places the three men in closer proximity to the masses [of soldiers] while still continuing a vivid, purposeful sense of physical distance and hierarchical distinction (Nichols 96). There is also the brilliant contrast between the masses in the crowds…and one person, Hitler.

Triumph of the Will premiered in March 1935 and was hailed a masterpiece; inspiring to some, while blood-chilling to others. Her film was considered an overwhelming propaganda success and brought many to the Hitler cause (Barnouw 105). On the other hand, she was scolded for it. No other film has been used by opposition forces as much as Triumph of the Will. “Nothing else depicted so vividly the demoniac nature of the Hitler leadership” (105).

I admire Riefenstahl and her intense efforts as well as creative abilities that were put forth in the making of the film. “She coordinated her forces with an almost maniacal drive and discipline, mirroring the atmosphere of the events themselves” (Barnouw 103). Not only did she practice impressive techniques, direction, and production, but she then spent five months on the editing process, making the film flow in a uniquely intriguing way, before the final product came to fruition. Moreover, I believe it took much bravery to do what she did, especially knowing she was most likely going to be greatly criticized for it in the end.

I found the 1993 interview with Riefenstahl to be very interesting – hearing what she had to say about the film and its’ representation of Hitler years later. She spoke of being intimidated by Hitler, especially when asked to work on such an epic project for the Reich. She said, “He radiated something very powerful … it was frightening” and went on to explain that she was afraid of losing her will and freedom in accepting and making the film. Fortunately for her, it turned out to be quite the opposite, in that she had much more freedom and special treatment than she probably ever imagined.