Reading Questions

1. What is the purpose of a designer, do they always work for a stakeholder?

The purpose of a designer is to create solutions to everyday problems, whether is be visually-based, digitally-based, or physically-based (or a combination therein). The designer works with a team of individuals in creating a vision for a product or visual design. Production costs, functionality, availability to consumers, marketability, and aesthetic appeal are just a few issues the designer must overcome to be successful. With so many moving parts, the designer cannot function in isolation, as George Nelson insists. The designer, unlike the artist, must always work for a stakeholder. Kees Dorst expands on this, explaining that “in design, your goals are partly determined by others, the stakeholders, because the things you create must fulfill some practical purpose in the wider world.” This is different, he explains, from the artist, who is free in their creation because “they do not aim for any practical application but strive to influence the feeling or thinking of an audience.”

2. Is the artist always a self-expressive narcissist?

I don’t think that the artist is always a self-expressive narcissist necessarily, but this does certainly seem to be the trend. This is especially evident in the claims set forth by Rick Poynor, of designart being a “one-way street.” There are no design galleries celebrating past and current designers and their works, no newspaper or online reviews of current and upcoming design, no major periodicals that have gained any sort of traction. Whether this is in fact due to a historical preference of art over design remains to be seen. What is clear is that if design is in fact merging with art, as Poynor suggests, there is a need to give it more adequate representation. As a result of this issue, the artist does indeed come across as a narcissist.

3. Can the designer/artist exist?

According to Donald Judd, the designer/artist can exist, but he stresses the importance of keeping the two ideas separate. He writes that “I am often asked if the furniture is art, since almost ten years ago some artists made art that was also furniture. The furniture is furniture and is only art in that architecture, ceramics, textiles, and many things are art. We try to keep the furniture out of art galleries to avoid this confusion, which is far from my thinking.” I agree with this stance, as the purpose of art is not to be functional. George Nelson explains this idea a bit further in stressing that “functional sufficiency is no guarantee whatever of good design.” So art in and of itself cannot function as design.

That being said, Judd himself is an excellent example of the designer/artist. One can be both, so long as one understands the need to separate the two. Art can inspire design, but it cannot become design. Joe Scanlan, who considers himself both a designer and an artist, provides further examples of other like-minded individuals experimenting with “design art,” as he calls it: Jorge Pardo, Tobias Rehberger, Heimo Sobering, Gregor Schneider, Angela Bulloch, and Franz West, to name a few. Scanlan argues that “[design art] attempts to expand the accessibility of art by contriving other, more pragmatic ways of engaging its reception and use.” While Scanlan believes in the ability to combine the two, he admits that “unfortunately, much design art does not function well enough to follow through on its promises…Andrea Zittel’s A-Z Living Units are so materially cumbersome and ergonomically cruel as to be laughably as anything other than art.” This statement brings us back to Judd’s original point, that while the two can exist within one mind, the ultimately are two very different fields that must be kept separate in order to each develop with any success.

Rick Poynor makes note of a peculiar phenomenon in the ever-developing world of “designart,” as he calls it. As evidenced by the media and numerous exhibitions, there seems to be some unwritten rule that allows artists for experiment in design, but not the reverse. Poynor theorizes that this is due to a long history of reviewing art (and not design).

Personal Reflection

1. What is your personal view of the difference between the designer and the artist?

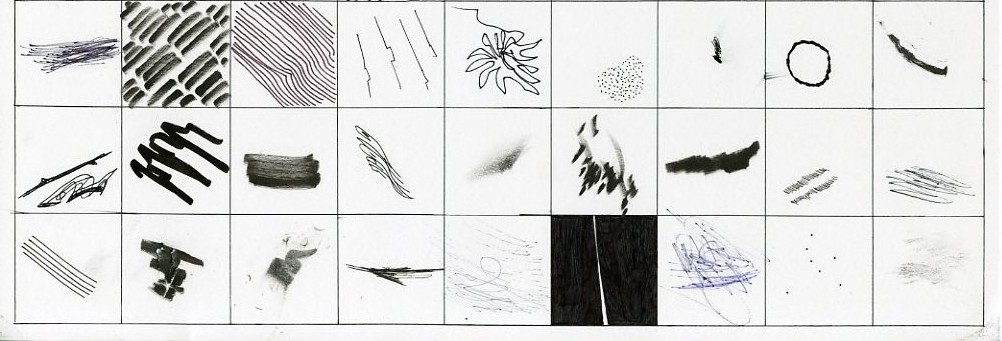

I see the designer and the artist as being two separate entities. A comment stood out to me in Norman Potter’s chapter, of how the difference between the designer and the artist can be seen in the concept of drawing. To the designer, it is used as a tool; a drawing is “a means to the end of manufacture, and their expressive content is strictly limited to the purposes of relevant communication.” To the artist, however, a drawing can be a finished product, a way of self-expressing. This example sums up my overall opinion on the difference between artist and designer. Design is painstakingly process-based, while art has fewer “rules.”

I’ve taken away from these readings that the designer and the artist can exist in one person, but the two occupations must be kept straight in one’s head to avoid creating poor work in either (or both) fields. To me, the designer is more methodical and infinitely more “business-driven.” The artist, however, seems to me less tied to formality, as art is not necessarily a solution to visual dilemmas (while design is). The artist is thus more free.

2. Which are you, why?

I am an artist rather than a designer. I see myself creating primarily to please myself, rather than to meet others’ needs. Although I see the merit in both occupations, the title of artist is more fitting to my desires and drives. Art is a necessary form of expression in my life, not the means to a production.