By: Katherine Wilson

Abstract

Revolutions of various types have occurred around the world throughout history. In 2010 a series of popular uprisings began in North Africa and across many countries of the Middle East that has come to be called “the Arab Spring.” This paper looks at the case of Egypt where the movement to topple long-ruling President Hosni Mubarak began in January 2011. Like other movements in the region, the case of Egypt has not been without casualties. The cause and nature of these casualties is unclear, however, and it is the purpose here to understand why. Through an analysis of news reports and eyewitness accounts in places such as Tahrir Square in Cairo, as well as social media, this paper investigates connections between governmental actions and the public responses, and the deaths that may have occurred as a result from clashes. Though the full story of deaths in Egypt may never be known – certainly not until the still-fluid situation stabilizes – international media attention on that country has begun to uncover the fates and stories of the dead in Egypt’s “Arab Spring.”

Download PDF: The Struggles of Revolution and Stories of the Dead

The Struggles of Revolution and Stories of the Dead

In the year 2014 global society lives in the media age. Whether social media or news media, the international community is capable of accessing and processing an enormous amount of information in any given day. Due to this connectivity very few things occur in the world that remain hidden or inaccessible to the general public, a consequence that Egypt’s government is increasingly familiar with. Thanks to globalization and the power of the information age, the international community has been kept abreast of the social and political upheaval in Egypt. Egypt’s government, currently led by interim President Adli Mansour and the military leader General El-Sisi, has been facing backlash due to actions or inactions taken during the revolution. One particular aspect of the revolution that has received frequent media attention has been the treatment of the dead. Zeinhom morgue is the primary forensics institute in Egypt, and has been the recipient of the many Egyptians who have died during the course of the revolution. Thanks to efforts by families and friends of the deceased as well as reporters and photographers tasked with following the consequences of the revolution, the international community has been given a chance to discover how an oft-forgotten part of society is treated in times of turmoil. Through media spotlights, the dead can now continue to tell their stories long after their bodies have failed.

An intricate web links the Egyptian government, globalization, revolution, and the dead. To understand the situation surrounding the deceased, a brief explanation of how the government, globalization, and the revolution tie into the equation is necessary. Egypt’s government from 1981 to 2011 was headed by Hosni Mubarak; during the course of his presidency the Egyptian people were subject to police scrutiny that seemed to have no limit as police were capable of arresting people without due suspicion (Noueihed and Warren 97). At the beginning of 2011 the public’s tolerance for these actions ran dry and resulted in the beginning of the Egyptian revolution, calling for Mubarak to step down and for a government that truly represented the people to step up (Logan; Noueihed and Warren 97). Following Mubarak eventually resigning as President the Egyptian military was temporarily left in charge of the country, with the promise to return power to a civilian government within six months (Noueihed and Warren 97-98). Initially, this news was met with acceptance and excitement from the Egyptian people; but as the months wore on and the military showed no sign of stepping down from power, protests began anew as Egyptians started to mistrust the absolute power the military seemed to wield (Noueihedand Warren 115). The military, once lauded throughout Egypt as a mostly-neutral source of power that was capable of keeping order, was starting to become as suspect as Mubarak.

Despite the new chaos that erupted in Egypt due to the military’s prolonged presence as a governing body, the promised elections eventually occurred sixteen months post-Mubarak with an interesting outcome: Muslim Brotherhood supporter Mohammed Morsi was elected (Noueihed and Warren 116). This election was the start of a new aspect of the Egyptian revolution. While Morsi was for all intents and purposes elected by popular vote, unrest continued to spread throughout Egypt due to several factors (Noueihed and Warren 98). In December 2012 Morsi had pushed through amendments to the Constitution that would in the future earn him the ire of the Egyptian people, several factions of Islam were fighting for majority presence, women and minorities were being marginalized, and increasing differences between social and age classes among the populace were becoming issues (Noueihed and Warren 99). By summer 2013 the Egyptian people – not including the Muslim Brotherhood who fully supported Morsi – had once again become disenchanted with their government and lead mass protests in an effort to remove Morsi from power (Kirkpatrick). The resultant turmoil and protests along with Morsi’s inaction lead to three significant actions. The Egyptian military removed the President from power, temporarily suspended the new Constitution, and put the chief justice of the Supreme Constitutional Court Adli Mansour in place as interim President (Kirkpatrick).

Source: Eleiba, Ahmed. “Egypt military laying groundwork for new transitional phse: Military analysis.” Ahram Online. Ahram Online, 1 Jul. 2013. Web. 28 Apr. 2014.

General El-Sisi, the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and Minster of Defense, initially claimed that the military’s actions were not a coup and that the military had no interest in continuing to interfere in politics (Kirkpatrick). El-Sisi said that they had taken Morsi out “because he had failed to fulfill the hope for a national consensus” (Kirkpatrick). National and international reactions to this military takeover were split; some were saying that it was an obvious military coup while others were calling it a necessary step to quell strife (Kirkpatrick). Tales of struggle, police brutality, and protest continued throughout the newest regime change. As of 2014, Egypt is still under control of the interim government instated by the military, with dates for elections for another new civilian government not yet set (Abdelaziz). Recently the military leadership council has given El-Sisi permission to run for President in the coming elections as long as he first retires from the military, though El-Sisi himself has not commented on whether or not he intends to put his name forth as a candidate (Abdelaziz).

With three drastic shifts in power in the space of three years, Egypt’s government faced a variety of changes and challenges. One of the challenges that the people in power had to contend with was social media. Through the use of facebook, twitter, and various news media outlets protestors managed to arrange demonstrations and rally support for change (Noueihed and Warren 106-109). Egyptian activists who took to the streets in the initial protests in 2011 had also managed to contact activists in Tunisia, the country that had successfully ousted their own unwanted government (Noueihed and Warren 108). Without the interconnectivity provided by modern technology and globalization Egypt’s revolution may never have gathered the numbers and support that was necessary to make the government take notice. On January 24, 2011 Egypt’s internet suddenly went down, likely an attempt by Mubarak’s regime to stifle support of the protests and an attempt to limit contact between Egyptians and with the world outside of Egypt (Noueihed and Warren 107). Mubarak, however, was only the first to try and stifle the power of globalization via an internet or media blackout. When the military detained Morsi and installed an interim government, they also removed the Muslim Brotherhood’s satellite television network from the air “along with two other popular Islamist channels,” arrested two Islamist TV hosts, and several people who “worked at a branch of the Al Jazeera network considered sympathetic to Mr. Morsi” (Kirkpatrick). While detained by the military, Morsi managed to send out a video over the intent condemning the military takeover and trying to convince listeners that he was still President and ready to “negotiate with everybody” (Kirkpatrick). Very soon after this video was posted, the hosting website was shut down and the video removed from the internet (Kirkpatrick). These instances demonstrate the power of social media and globalization and also highlight how Egypt’s government, regardless of who is in charge, is fully capable and willing to attempt to suppress communications.

With a brief history of Egypt’s recent governmental changes and examples of how social media (and thus globalization) have aided or hindered the process, the ties to death throughout the revolution are easier to see. Throughout all three of the regime changes since 2011, the number of dead Egyptians has increased due to police-protestor, military-protestor, and even protestor-protestor clashes (Noueihed and Warren 96-133; Kirkpatrick). The government’s actions have led to dissent among the Egyptian populace, the Egyptian populace has utilized social media and news reports of Tunisia’s successful revolution to rally support and send out a call to arms, and the government as well as the military has taken steps to control the situation through violence and/or intimidation. The rest of this paper will be dedicated to outlining some of the incidences that have led to Zeinhom’s, and by extension the Egyptian government’s, poor reputation in regard to dealing with the dead.

Source: Londono, Ernesto. “Egyptian Man’s Death Became Symbol of Callous State.” Washington Post. Washington Post, 9 Feb. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

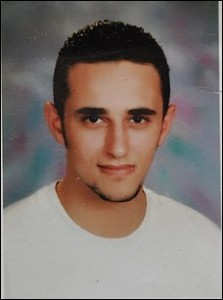

The first event that received widespread international attention was the death of Khaled Said in 2010, a young man who was “beaten to death…by two policemen on a public street” during President Hosni Mubarak’s regime (Logan). Said’s death is widely touted as one of the sparks that ignited the Egyptian revolution that ousted Mubarak (Logan). The story behind Said’s death begins with a video he posted online that depicted “policemen allegedly sharing the spoils of a drug bust” (Logan). In June 2010, Said was removed from a public internet café by plainclothes policemen and beaten to death (The Guardian). Said’s family managed to obtain a picture of his face by bribing a guard at Zeinhom morgue; the photo depicted Said’s face, deformed and showing signs of a severe beating (Londono). This photo quickly circulated throughout Egypt and became the representation of police brutality, and a symbol around which Egyptians could gather to protest their treatment by the government (Logan). Police and forensic expert Mohammad Abdul Aziz with Zeinhom morgue claimed that Said’s cause of death was asphyxiation due to swallowing a bag of drugs before he was taken by the police (Gaber). However, people who witnessed the beating claimed that Said’s head was repeatedly smashed against first a marble table and then stone steps (Londono). Due to the controversy surrounding the case an independent forensic examination was done of Said’s body; this independent report claimed that Said’s body showed signs that the bag of drugs was forced into his throat post-mortem (Salem). Both the eyewitness accounts as well as the independent report disagree with the official police report and the report of the police-affiliated forensic expert; this disparity in information further incited the public to call for an international inquiry into brutality from government security forces (Gaber). This situation became a common occurrence during the revolution: Egypt’s officials would take a stance that did not implicate them in any wrongdoing, while the bodies of the victims provided evidence of violence and brutality.

Source: The Guardian. “Anger in Egypt as Police Who Killed Khaled Said Get Seven Years.” The Guardian. Guardian News, 26 Oct. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

As of today the outcome of the trial of the two policemen who allegedly beat Said to death is unknown due to a lack of available information on their situation. The initial trial in 2011 found them guilty to charges of unlawful arrest and excessive brutality and they were to serve a seven year prison sentence (Salem). However, an appeal brought the two men – Mahmoud Salah Amin and Awad Ismail Soliman – back to court for a retrial in December of 2013 but the retrial was postponed for several days due to the unauthorized presence of protestors outside (Salem). The protestors were said to have disrupted the streets around the area and injured an officer; several of those protestors were detained by police and/or injured when police used a water cannon, tear gas, and birdshot to disperse the crowds (Salem). The retrial was set to be completed on December 4, 2013, but no further news has surfaced regarding the outcome (Salem).

Khaled Said’s case was only the first to gain wide-spread media attention. Throughout the regime changes – Mubarak to Morsy to El-Sisi – a frequent source of controversy that links Egypt’s government to conspiracy and cover-ups among the deceased victims of the revolution is Zeinhom morgue. Located in Cairo, Zeinhom morgue is the primary forensics institute for the region and is a frequent source of protest from the people (Nordland). To better understand why the events surrounding Zeinhom have horrified not just Egyptians but also the rest of the world, three topics will be discussed: the general corruption of the institution, the correct way to handle mass casualties according to an internationally accepted source, and the basics of some Islamic traditions surrounding death. These topics on their own are capable of inducing debate, disagreement, and dissension. Combined into one social quagmire it evolves into a complicated and sensitive dilemma.

Source: Al-Abd, Rania Rabih. “Egypt: Tales of Death at Zeinhom Morgue.” Al-Akhbar English. Al-Akhbar, 24 Aug. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

When researching on Zeinhom morgue, news articles from various outlets and countries are always the first to appear. One article says that Zeinhom morgue was protected by “nameless young men” who did their best to “make sure no one approached the building” (Nordland). These young men were described as “hired government thugs” by people trying to collect deceased love ones; the writer claims that attempting to speak with the men resulted in either politely worded demands to leave the premise or in outright threats of retaliation (Nordland). Another article describes how overcrowded Zeinhom became because of the sudden influx of bodies; there was no more room within the morgue itself, so bodies had been lined up on the street outside or left in piles in refrigerated trucks (al-Abd). Families who have been tasked with identifying family members or friends claim that the death certificate that Zeinhom produces often doesn’t match the story the bodies tell; bullets pulled from bodies disappear under orders from Egyptian security forces and obviously burned bodies were put down to an overdose of tear gas (Fathi; Fisk). Some families were forced to accept suicide as cause of death when it was well known that their loved one was shot during a protest (Nordland; al-Abd). Whether or not the employees of Zeinhom want to behave as they do and assist in covering up crimes is unclear, but stories remain sure that Zeinhom is complicit in burying or losing evidence and fabricating forensic reports (Fathi).

Besides fabricating forensic reports, Zeinhom has also come under fire due to the way they have treated the dead. Reporters and families have given statements that say unwrapped bodies were simply piled one on top of the other in the morgue, and often not even kept in refrigerated rooms; also, once morgue capacity was met bodies were simply laid on the streets outside and piled into refrigerated trucks (Fathi). Individuals who have managed to gain access to the morgue and observe an autopsy or the ghusl (an Islamic ritual that is supposed to be done before burial) say that the bodies are treated with disrespect and that the Egyptian and Islamic culture of respecting the dead are being blatantly ignored (Fathi). Families, if they are even allowed near the morgue, are forced to wander among the dead and decomposed in order to identify someone (Fathi). To better understand the severity of the situation, a comparison using Zeinhom’s practices and an internationally accepted report on mass casualties will be done.

According to a manual supported and funded by the Pan American Health Organization, the World Health Organization, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies there are protocols that can be followed in the face of mass casualties. The report says that bodies should be kept cool in order to slow decomposition, which makes facial identification difficult if not impossible; cold storage can be found in refrigerated rooms at the morgue or in refrigerated trucks (Morgan). However, if cold rooms aren’t available due to lack of space, the deceased can also be temporarily buried at 1.5 meters deep and a minimum of 200 meters from drinking water because underground is much cooler than above ground and can help slow decomposition (Morgan). While people might think piling ice on the dead would help preserve them, the manual asserts that using ice could “damage bodies and personal belongings” and create “large quantities of dirty waste water” that could spread disease and create disposal issues (Morgan). Instead, dry ice can be used to temporarily preserve remains by building low walls around small groups of bodies and covering the entire construct with a tarp (Morgan). Regardless of what choice of storage is chosen, each body should be wrapped separately and labeled with an identification number (Morgan).

Zeinhom has followed very few of these recommendations. While refrigerated trucks have been provided for storage, the morgue still faces a capacity problem and thus there are bodies that are not kept stored at the proper temperature or in the proper location. Mourners in the street are allowed to pile bags of ice on the dead, which could lead to contaminated waste water and damage to the bodies and any belongings. Also, according to reporters unwrapped bodies are simply piled one on top of the other without any kind of identifying tags assigned or individual shrouds being used to prevent cross-contamination (Fathi; Nordland).

Identification of the deceased is another problem that must be faced during mass casualties. If possible, facial identification should be done within a few days of death to minimize difficulties following decomposition (Morgan). If no other options are available due to the extremity of the situation it can be acceptable to allow families and friends to view the decedent in person to make the identification, though use of well-taken photographs of faces and unique markings on the body (tattoos, scars, birthmarks) and personal belongings are the preferred method to minimize psychological damage to the living (Morgan). Zeinhom has previously kept people from making identification before decomposition erases the face and frequently the only way to identify a loved one is for a family member to walk among the dead and move bodies around to physically search for a missing person; the time it takes for families to find deceased members puts further strain on the issue because the Muslim faith dictates that the deceased should be buried within a few days of death (Fathi). Details regarding this particular issue will be given later in the paper. Another failure of the bureaucracy that manages Zeinhom is in media relations and public notice. According to the manual, public relations officers should be appointed in order to distribute appropriate information regarding the situation to both local and national audiences (Morgan). A working relationship with the media is necessary in order to ensure the dissemination of accurate information and prevent the spreading of unnecessary panic or false information (Morgan). Information shared with the public should include a list of confirmed dead, instructions on how to claim the body, and information about the “processes of recovery, identification, storage, and disposal of dead bodies” (Morgan).

Zeinhom and the officials responsible for administrative tasks as well as government representation have either not done any of the recommended public relations or they have done it incorrectly. The “nameless young men” who are purported to be government thugs work to scare people away from the morgue and to prevent reporters and photographers both from getting inside Zeinhom and from speaking with the mourners at the scene (Nordland). Egypt’s government has attempted to report lower numbers of the dead and to place blame for the incidents on the deceased (Nordland). Government supporters have tried to “hijack the [media] and steer it that way” in an attempt to keep the international community from realizing the scope of victims during protestor-government clashes (Nordland). If anything, statements from reporters, photographers, and even mourners located on scene at Zeinhom indicate that the government is actively trying to hide information and prevent the spread of information regarding the deceased. In the long run, this course of action could lead to further public dissent and exacerbation of the already present problems.

Source: Abd-Allah, Abdel Halim H. “In Pictures: Zeinhom morgue post 25 January anniversary.: Daily News Egypt. Daily News Egypt, 27 Jan. 2014. Web. 26 Apr. 2014.

Aside from the corruption of the individuals responsible for running the morgue and the apparent disregard for typical emergency responses to mass casualties, Zeinhom faces condemnation from the Muslim community due to its disrespect for Islamic traditions in the face of death (Fathi). Islam dictates that very specific steps must be taken when a Muslim dies, and for the most part these steps are the same for men and women, adult and child (Siala). The process differs slightly when the death is unexpected and when the body in question is housed in the morgue versus expected and at home or in a hospital, but there are certain aspects that must be observed regardless (Siala). There are two particular aspects of post-mortem traditions that have been interfered with by Zeinhom. The first relevant aspect of the Islamic traditions is al-ghusul, the washing and cleansing of the body; this process involves washing the decedent an odd number of times with water and perfumes (Siala). This is generally supposed to be done soon after death, but due to the nature of the situation at Zeinhom some families have had to wait days if not weeks to perform the ritualistic cleansing for their deceased loved ones (Siala; Fathi). The second aspect is the belief that the decedent must be buried soon after death, within a few days is preferable (Siala). With the long lines of dead waiting for autopsy at Zeinhom, it is for the most part impossible to claim a body in a quick and reasonable manner.

The situation surrounding Zeinhom and the treatment of the dead is complicated due to multiple factors. In this kind of event, the interactions and behaviors of the public, the media, the government, and any responding officials can become murky and confusing. With multiple sides all trying to vie for attention or get their version of events out to the public, facts can become shady and unreliable. Since the Egyptian government is attempting to stymie international media attention on Zeinhom morgue and multiple sources are writing about their experiences at the scene or commenting on statements from local sources, the international community is left to draw its own conclusions (Nordland). Due to the reputation of the Egyptian government and the conflicting stories emerging from numerous media outlets, it is impossible to know exactly what is going on behind the scenes at Zeinhom. Sheikh Said, the head man responsible for performing ghusul at Zeinhom, says that while people criticize the morgue frequently Zeinhom was “the first to support the revolution” and that “the morgue is well equipped. Don’t believe anyone who says the conditions [in Zeinhom] are bad” (Fathi). On the other hand Nazly Hussein, an activist who frequently aided families who had to deal with Zeinhom, says this about Zeinhom: “This room is horrible. The bodies are on the gurneys, but men are also thrown on the floor…Egyptian culture teaches us to respect…the dead. But in the morgue, I never see any respect…” (Fathi). Here are two different people with two different opinions, and no way for the international community to truly determine which one – if either – is right. Despite all of these difficulties in assessing the situation, the international community owes its awareness of Zeinhom and its woes to globalization and the ability to transmit information from country to country on a world-wide scale at a very fast rate.

The Egyptian revolutions will likely leave a long-lasting impression on both the country itself and on the international community. Egypt’s place in the history books was assured simply by being a part of the Arab Spring, a phenomenon that has received continuous and widespread coverage in the media. The events that have occurred throughout the country’s revolution reflect the situations found in other Middle Eastern countries that are also undergoing rapid changes, especially the body count due to government and non-government factions. While Egypt’s struggle continues, once the country has settled into some semblance of order the consequences of the revolution will continue to be felt both locally and internationally for years to come if only because of the significant number of victims of a desperate government. Many of the dead are from the youth population, which was a significant part of the protests; a young man’s death – Khaled Said – was even one of the initial driving forces behind the start of the revolution (Gaber). Revolution often reflects dissatisfaction with aspects of politics, religion, and/or society. In particular, Egypt’s recent turmoil has covered issues like civilian and military authoritarianism, economic crisis, youth movements, human rights and human rights violations, and government-wide corruption. Zeinhom’s treatment of the victims of revolution encompasses all of those issues, and will likely be remembered as an institution that was representative of a corrupt government and a tool used to stifle the voices of the dead.

Works Cited

- Al-Abd, Rania Rabih. “Egypt: Tales of Death at Zeinhom Morgue.” Al-Akhbar English. Al-Akhbar, 24 Aug. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/16817>.

- Fathi, Yasmine. “Guardians of the Betrayed Dead: Inside Cairo’s Zeinhom Morgue.” Ahram Online. Ahram Online, 2 Sept. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/151/79876/Egypt/Features/Guardians-of-the-betrayed-dead-Inside-Cairos-Zeinh.aspx>.

- Fisk, Robert. “Egypt Crisis: A National Tragedy Plays Out at Cairo’s Stinking Mortuary.” The Independent. Independent.co.uk, 19 Aug. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/egypt-crisis-a-national-tragedy-plays-out-at-cairos-stinking-mortuary-8775128.html>.

- Gaber, Sherief. “Deaths without Dignity.” Mada Masr: Independent, Progressive Journalism. N.p., 21 Aug. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.madamasr.com/content/deaths-without-dignity>.

- The Guardian. “Anger in Egypt as Police Who Killed Khaled Said Get Seven Years.” The Guardian. Guardian News, 26 Oct. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/26/khaled-said-police-sentenced>.

- Kirkpatrick, David D. “Army Ousts Egypt’s President; Morsi is Taken into Military Custody.” New York Times. New York Times Company, 3 July 2013. Web. 14 Feb. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/04/world/middleeast/egypt.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>.

- Logan, Lara. “The Deadly Beating That Sparked Egypt Revolution.” CBS News. CBS Interactive, 2 Feb. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-deadly-beating-that-sparked-egypt-revolution/>.

- Londono, Ernesto. “Egyptian Man’s Death Became Symbol of Callous State.” Washington Post. Washington Post, 9 Feb. 2011. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2011/02/08/AR2011020806360.html>.

- Morgan, Oliver, Morris Tidball-Binz, and Dana Van Alphen, eds. Management of Dead Bodies after Disasters: A Field Manual for First Responders. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organizations, 2006. ICRC. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/icrc_002_0880.pdf>.

- Nordland, Rod. “At Cairo Morgue, Families Face Menace from Nameless Men.” New York Times. New York Times Company, 20 Aug. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/21/world/middleeast/at-cairo-morgue-families-face-menace-from-nameless-men.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&>.

- Noueihed, Lin, and Alex Warren. The Battle for the Arab Spring: Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Making of a New Era. Cornwall: TJ International Ltd., 2013. Print.

- Salem, Mostafa. “Khaled Said Trial Postponed until 4 December.” Daily News Egypt. Daily News Egypt, 2 Dec. 2013. Web. 11 Dec. 2013. <http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2013/12/02/khaled-said-trial-postponed-until-4-december/>.

- Siala, Mohamed Ebrahim. “Authentic Step by Step Illustrated Janazah Guide.” About. About. N.d. Web. 13 Feb. 2014. <http://islam.about.com/gi/o.htm?zi=1/XJ&zTi=1&sdn=islam&cdn=religion&tm=162&f=10&su=p284.13.342.ip_&tt=2&bt=5&bts=45&zu=http%3A//www.missionislam.com/knowledge/janazahstepbystep.htm>

Biography

Although interested in the humanities, history, and anthropology, my greatest interest has always been forensics. First and Loyola University and then at St. Edward’s University, I studied chemistry, biology, criminal justice,forensics, humanities, and more. I was a founding member of the Forensic Association Committed to Truth and acted as the Community Service officer. I am also a member of Alpha Chi and Alpha Phi Sigma, the National College Scholarship Honor Society and the National Criminal Justice Honor Society respectively. I graduated cum laude from St. Edward’s in December 2013 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Forensic Science.

Although interested in the humanities, history, and anthropology, my greatest interest has always been forensics. First and Loyola University and then at St. Edward’s University, I studied chemistry, biology, criminal justice,forensics, humanities, and more. I was a founding member of the Forensic Association Committed to Truth and acted as the Community Service officer. I am also a member of Alpha Chi and Alpha Phi Sigma, the National College Scholarship Honor Society and the National Criminal Justice Honor Society respectively. I graduated cum laude from St. Edward’s in December 2013 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Forensic Science.

After honing my skills in a crime lab for a few years, I plan to attain a Master’s degree in Forensic Document Examination. My goal is to specialize in questioned document examination so that I can eventually work in the field of historical forensics to focus on authentication of old documents.