The Russian Revolutions written lecture and linked PowerPoint

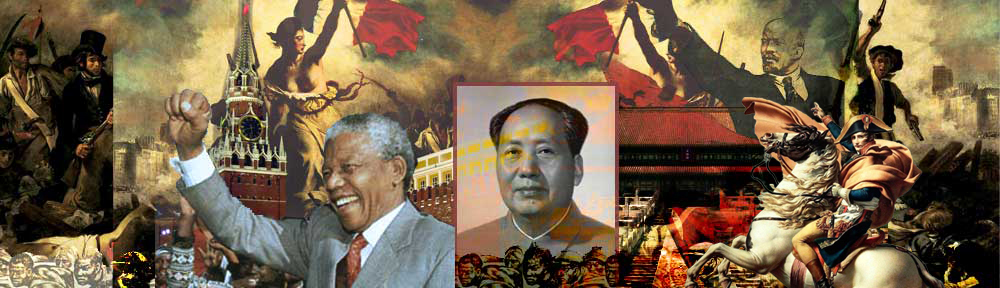

In many ways the Russian Revolution had as profound an effect on the twentieth century as the French Revolution had on the nineteenth century. While in the nineteenth century, heads of governments feared the spread of the ideas of the Mountain (Jacobins), for much of the twentieth century, numerous governmental leaders feared the spread of Bolshevism (communism).

The Russian Revolution provided the first successful example of a communist revolution, and it became a model which many third world countries followed in their attempts at rapid modernization. Since, like the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution was accompanied by a proselytizing zeal, U.S. foreign policy became partially shaped by a fear of communism; and we tried to prevent other countries from following the Soviet example.

This helps to explain our involvement in Korea, Cuba, Viet Nam, Nicaragua, and a number of other places. Looking back to Russia in 1917, it is not surprising that a revolution occurred; what is surprising is why it did not occur sooner. There were deep seated signs of revolution and revolutionary protest. Some historians date the first revolutionary attempt to the Decembrist Revolt in December 1825, just after the death of Tsar (pronounced Zar) Alexander I when dissidents were calling for “Constantine (Alexander’s brother) and the constitution” (Thompson 133). A number of those involved in this revolt had been army officers, who having returned from the wars against Napoleon, wanted “liberty, fraternity, and equality” from their government.

They were not hoping to establish a republic or democracy, but rather a constitutional monarchy. The Decembrist Revolt was supported by members of the growing Russian intelligentsia which included some of the army officers, other liberally educated nobles, and some members of the tiny middle class. This revolt was brutally suppressed by the new Tsar, Nicholas I. At this time the population of Russia was about 41,000,000, almost 37,000,000 of whom were serfs or state peasants (Thompson 135).

In 1861, Tsar Alexander II (called the Reformer Tsar), liberated the Russian serfs. Unfortunately, the emancipation did not greatly improve the lives of the former serfs; they were forced to pay onerous exemption dues to their village commune so that the nobility could be reimbursed for their land by the government. Some moved on to the cities to work in the few industries that then existed in Russia.

Most, however, stayed in the countryside, where, by the last decade of the century, their numbers were growing by as many as 800,000 a year. By 1905, the Russian population had exploded to approximately 105,000,000. Of these, about 100,000,000 were peasants, and 2.25 million were urban workers (Thompson 161-163). With this population boom, the peasants needed more land.

Those who moved to the cities to seek a better life, found deplorable work and living conditions. Although there was some industrialization in cities like St. Petersburg and Moscow, and a few places in the Ural mountains, most of Russia was much like it had been for centuries. Farming methods were extremely backward, and the farms had very low productivity. Until 1905, former serfs, their children and their grandchildren, still had to pay redemption dues that dated from the time of the emancipation.

Adding to this economic picture was the fact that the industrialization in Russia was based mostly on foreign and state investment, rather than coming from a native entrepreneurial class. There were droughts and economic depression in the first years of the twentieth century. In 1904, Tsar Nicholas declared war on Japan, which was considered a backward island nation. By 1905, the Russians had not beaten the Japanese, and this became a source of embarrassment for the tsar as well as a source of debt for the country.

Throughout the nineteenth century, dissident groups formed in Russia. In 1881, Alexander II, the Reformer Tsar, was assassinated by members of the radical People’s Will. Ideas such as anarchism and Marxism were taking root against the autocratic government. Tsars Alexander III (1881-1894) and Nicholas II (1894-1917) responded by increasing state repression. In 1905, when approximately 100,000 workers marched to the palace to petition Tsar Nicholas for better wages and working conditions, the palace guards panicked, and fired into the crowd, killing approximately 100 of the unarmed demonstrators (Thompson 177).

This event, called “Bloody Sunday” signaled the beginning of what was termed the Revolution of 1905; it also ended the belief in the tsar as the caring father figure. By October 1905, Nicholas II was forced to sign the October Manifesto, which created a constitutional monarchy; he was to share power with an elected legislature called the Duma. Although Nicholas II promised reform, he did not support the Dumas, and disbanded the first two after only a few months of deliberation.

The third Duma lasted its four year term, and the fourth Duma was cut short by the outbreak of World War II. Under Prime Minister Stolypin land reform was beginning to occur, but these efforts were ended by the outbreak of World War I. Conditions in the factories remained among the worst in the world. In addition to these problems, Russia was a multinational country with over 125 national/ ethnic groups, many of whom were calling for some autonomy.

Russia’s entry into World War I exacerbated many of Russia’s problems. Nicholas II, who was a weak and ineffectual leader, hated administering the country, but loved to play military commander. He went off to the front, and left the running of the government in the hands of incompetent ministers, and later to his wife, Alexandra.

Alexandra, the granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and cousin of the German Kaiser, was seen in a very unfavorable light. Because of the hemophilia of her son, the heir, Alexis, she had placed her confidence in the demented, irreputable monk, Rasputin. She believed that Rasputin was the only one who could help her son recover from bouts of severe hemorrhaging. The hold that Rasputin seemed to have over the tsarina made her and the tsar the brunt of ridicule.

Much like Marie Antoinette, who was called the “Austrian woman ” at a time when France was at war with the Austrians, Alexandra was deridingly called the “German woman” when Russia was fighting the Germans. Nicholas II, like Louis XVI, was characartured as a cockhold. Approximately 15 million Russians fought in World War I. Of these, about half were “killed, wounded, and taken prisioner” (Thompson 188). Russian troops suffered from harsh punishment and poor leadership; they were often unpaid and without boots, rifles, ammunition or food. Initially the soldiers supported the war, but by the summer of 1917, there was a growing sense of injustice among the troops.

The war helped to cause severe inflation and food shortages and “intensified the sense of injustice and resenment that had been biulding around the russian masses in the previous decades” (Thompson 190). By March 1917, protests in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) occurred over the shortage and price of bread. These demonstrations were coupled with workers’ strikes. Soldiers were ordered to fire on the protesters; instead they joined them. A few days later, lacking support, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated; and the 314 year Romanov Dynasty ended. The Provisional Government that replaced the tsar, inherited all of the tsars problems, but little of his power.

Moderates within the Provisional Government felt they should wait for the people to elect the Constituent Assembly so that Russia’s problems could be addressed. The Provisional Government, then, took no action about the demands of the peasants for land; the demands of the soldiers for an end to the war and harsh discipline; the demands of the workers for better conditions and pay,and representation in the factories; and the demands of the ethnic/national minorities for autonomy.

When Lenin returned to Russia in April 1917, he said that the Bolsheviks should not participate in the Provisional Government, which was becoming increasingly ineffective and unpopular. Lenin rallied Russians with his call for “peace, land, bread, and power to the worker’s soviets.” He promised the people exactly what they wanted. In the summer of 1917, there were street demonstrations against the war and the Provisional Government.

In the fall of 1917, Prime Minister Kerensky’s reputation was tarnished by the foiled counterrevolutionary coup of General Kornilov. By October 1917 when the Bolsheviks toppled the Provisional Government, this government had very little support. Lenin soon abolished the long awaited democratically elected Constituent Assembly; established the one party Bolshevik (communist) rule; and withdrew the Russia from the war with the Treaty of Brest Litovsk. Under this treaty, Russia lost a quarter of its land and population (Thompson 105). Soon civil war broke out between the Bolsheviks and the White Army, which was supported by the U.S., France, and Great Britain.

Work Cited

Thompson, John. Russia and the Soviet Union. 5th Ed. Boulder: Westview Press, 2004.